Jun 24, 2024

Macklem: BOC can beat inflation without unemployment spike

, Bloomberg News

Outlook for upcoming data on Canada's economy

Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem said the country’s economy is headed for a soft landing, suggesting the central bank expects the unemployment rate to rise but that a large increase isn’t needed to achieve the inflation target.

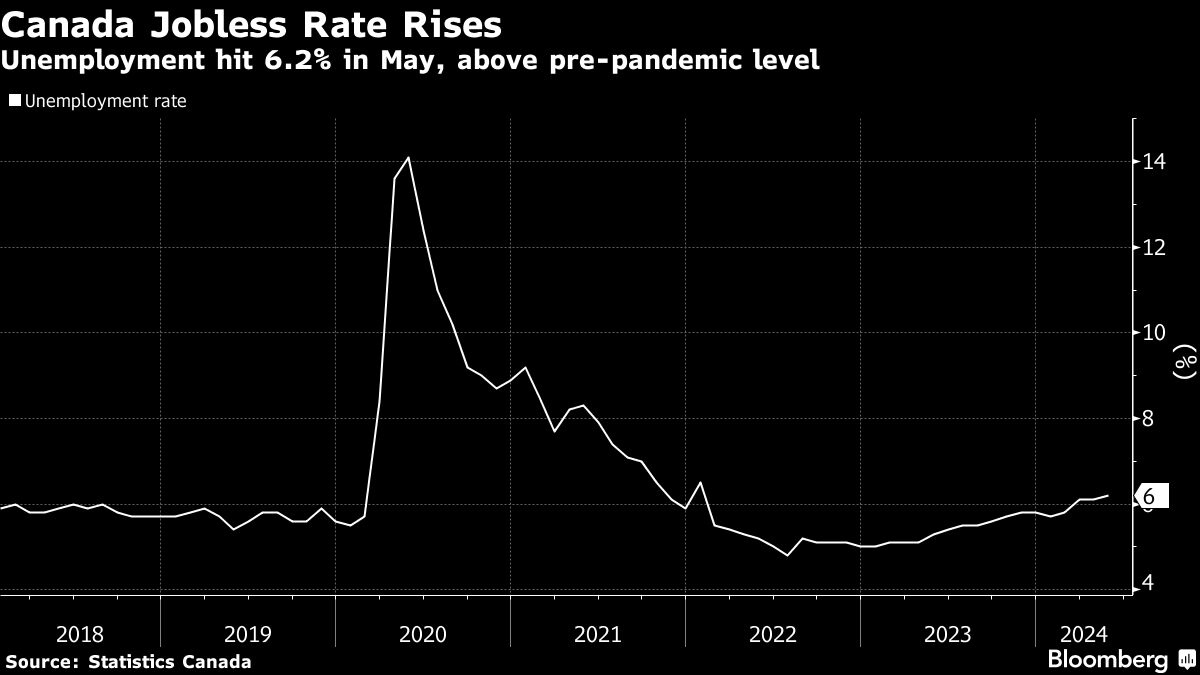

On Monday, Macklem said Canada’s unemployment rate — which hit 6.2 per cent in May — was “just above” pre-pandemic levels, when the labor market was close to “maximum sustainable employment” — the highest level of jobs an economy can have without stoking inflation.

“We continue to think that we don’t need a large rise in the unemployment rate to get inflation back to the 2 per cent target,” Macklem said in a speech he delivered in Winnipeg.

Canada’s labor market has loosened and is “closer to being in balance,” he said. It’s harder to find a new job, which is particularly affecting young workers and newcomers who are facing unemployment rates that are rising faster than those of other Canadians, he added.

The speech suggests the Bank of Canada is increasingly confident that the country’s labor market has loosened sufficiently to allow a further cooling in inflation, even as the economy continues to grow and add jobs. Speaking to reporters after the speech, Macklem said it’s reasonable to expect further interest rate cuts if price pressures continue to ease.

“We don’t want monetary policy to be more restrictive than it has to be,” Macklem said. At the same time, officials don’t want to lower borrowing costs “too quickly” and jeopardize progress on inflation, he added.

Macklem said that while the bank sees sticky wage growth above pre-pandemic levels, the rebalancing of the labor market and lower inflation is starting to moderate compensation pressures.

“Wages tend to lag adjustments in employment,” Macklem said. “Going forward, we will be looking for wage growth to moderate further.”

Faster growth in the unemployment rates of newcomers means Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s federal government “has some room” to slow the growth of non-permanent residents without causing labor shortages or tightening the labor market, he said.

“There are limits to how quickly we can absorb people into the economy, there are limits to our immigration policy,” Macklem told reporters, adding that the population inflows been a “key source of growth.”

He also acknowledged that recent immigrants and young people are also most likely to be renters — a group the bank said is facing more household financial stress.

Macklem also said that the labor market “overheated” after what the bank called “exceptional” fiscal and monetary policy responses. That drove up job vacancies, a big reason the federal government ramped up the number of newcomers brought into the country.

The number of job vacancies is now falling, a trend the bank expects to continue. That will accompany further increases in the unemployment rate, according to policymakers’ analysis of the Beveridge curve.

In the long run, Macklem said Canada needs to “keep investing” in an inclusive labor market, “smart immigration” and a “strong and accessible education system” in order to tackle the country’s productivity problem.

In June, the Bank of Canada was the first Group of Seven central bank to start cutting interest rates, lowering its policy rate to 4.75 per cent. The bank next sets rates on July 24.