Oct 28, 2022

DeSantis Keeps Edge in Florida Race as Clock Ticks on Home-Insurance Crisis

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- When Hurricane Ian slammed into southwestern Florida, its beleaguered home-insurance market didn’t seem to stand a chance.

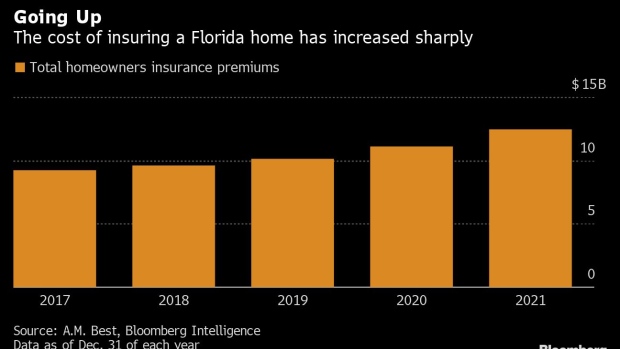

Efforts to repair the system by Ron DeSantis -- the Republican governor expected to make a presidential run -- had floundered, with the market still beset by scams, expensive insurance policies and a retreat by the largest firms. Average homeowner premiums in the state surged 33% from last year to $4,231, nearly triple the national average. At least a half-dozen insurers that do business in Florida have been declared insolvent already this year, with Ian threatening to push more over the brink.

As the storm wreckage is cleared, policyholders are scrambling to collect on claims, while DeSantis and the statehouse rush to address the crisis. A special session will consider providing tax relief to those whose properties were destroyed by the hurricane and potentially to implement further reforms.

DeSantis’s handling of the insurance crisis provides easy fodder for political opponents, who say he focused too much on culture-war issues, including a state law critics have dubbed “Don’t Say Gay” that limits instruction about gender identity and sexual orientation in kindergarten through third grade. Yet it’s unclear whether the criticism is sticking with many voters as the Nov. 8 gubernatorial contest approaches. Polls show DeSantis with a wide lead over Charlie Crist, a Democrat.

“I don’t think between now and Election Day, it’s going to make any difference. It’s a complicated issue,” said Brad Coker, managing director of consulting firm Mason-Dixon Polling and Strategy, referring to the insurance crisis. “You can run off a litany of issues that people kind of know there’s this side and there’s that side. Insurance, it’s not the same.”

A spokesman for the governor defended his efforts, pointing to the reforms put in place so far.

“Even the most aggressive reforms will take time to affect the insurance industry,” Bryan Griffin, the governor’s press secretary, said in an email. “The 2021 and 2022 legislative efforts will be effective. The governor expects the legislature to continue its work and pass reforms that will stabilize the property insurance market further and ensure that Floridians have ample options for affordable property insurance coverage.”

Unfolding Crisis

Florida’s insurance crisis was unfolding long before Ian made landfall on Sept. 28 near Cayo Costa, killing at least 118 people in the state. The smaller companies that do the bulk of underwriting in Florida are inundated by litigation that has driven them to stop writing policies in the state and forced some out of business. Insured losses from the storm, estimated to be in the tens of billions of dollars, threaten to further destabilize the situation.

Top underwriters had already wised up to the threats. Progressive Corp. in August called Florida “especially painful” and said it had begun implementing a plan to shrink its business there in favor of less-volatile states. Allstate Corp. CEO Tom Wilson said last year that the company recognized it had too big a market share in Florida, “which of course sticks out into the ocean like a thumb.” But its market share in the state is less than 3%, and Ian caused only an estimated $366 million in catastrophe losses, net of reinsurance.

State-backed Citizens Property Insurance Corp. accounts for slightly more than 10% of the Florida homeowners insurance market by premiums written, despite being intended to serve as a backstop to the private insurance market.

As it takes on more risk, residents could be on the hook for costs. State law requires the company to levy assessments when it experiences deficits in the wake of a major storm or disaster. Citizens Property said earlier this month it won’t need to levy surcharges on its policyholders or assessments on other Florida policyholders to cover claims brought on by Ian.

The implications go beyond Florida. The Treasury Department’s Federal Insurance Office this month said it’s seeking comment on a plan to collect data from insurers to assess climate-related financial risk, a move to evaluate whether homeowners have enough insurance protection against global warming. Secretary Janet Yellen said Ian highlighted the need for a better grasp of insurance market vulnerabilities in the US.

DeSantis Test

Unless DeSantis and state lawmakers find a solution, Florida risks additional insurer departures, even higher premiums and strains on its insurer of last resort.

In 2021, DeSantis signed a bill into law meant to prevent contractors from roping consumers into insurance scams that promise a “free” roof paid for by their underwriter. In a May special session, lawmakers authorized a $2 billion reinsurance backstop for hurricane losses along with other rules meant to aid flailing insurers.

Benefits from those new policies have yet to materialize, said Mark Friedlander, a spokesman for the Insurance Information Institute. He added that the excessive levels of insurance litigation and the payouts that motivate those cases still haven’t been addressed by lawmakers.

“We’re seeing no results at this stage,” Friedlander said. “The question is, will it bring stability in the future? That’s unknown.”

The crisis has left DeSantis vulnerable to broadsides from political rivals who accuse him of letting efforts to overhaul the insurance system fall to the wayside in favor of waging a culture war. In addition to the “Don’t Say Gay” law, DeSantis signed into law a ban on abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy and approved a resolution prohibiting state pension funds from screening for environmental, social and governance risks.

“Everybody watching tonight knows that your property insurance is up under him. That’s the problem. He could have addressed it in the regular session; he didn’t,” Crist, who is challenging DeSantis for the gubernatorial seat, said in a debate against the incumbent Monday. “I don’t think the third time’s going to be the charm because his focus is not on Florida. It’s not on you.”

The dysfunction in the market is taking a toll on some of the state’s most vulnerable residents.

Sandy Reeves, 71, and husband Richard, 70, moved to a Fort Myers country club in March of 2021 with plans to enjoy retirement, less than a year before a tornado tore through their home in January.

The couple had been embroiled in an insurance dispute to recoup $230,000 of damage costs from that tornado. Then Ian hit their home in September and destroyed nearly all of the couple’s furniture, leaving just a bed, a lawn chair and an office chair functional.

“A wall broke in the garage behind the refrigerator, and that’s when the floodwaters came in. We had four feet of water in the house, just gushing in,” Sandy Reeves said. “My sister, who’s a diabetic, my husband, who has Parkinson’s, and myself -- we were standing on ladders until the water receded. You ever see rapids in Colorado? That’s how the water was flowing.”

So far, there’s little evidence the insurance challenges will hurt DeSantis’s political ambitions. A University of North Florida poll published Wednesday put the incumbent ahead by 14 percentage points, a rarity in notoriously tight Florida elections. Throughout the campaign, DeSantis has enjoyed enthusiasm within the party for his political ascent, as some see the governor as a GOP presidential contender.

Rebecca Saenz, a 60-year-old Wimauma resident whose residence was affected by the hurricane, said she doesn’t identify with a political party and is still undecided on the race for governor. “I’ll vote for whoever can do some changing on insurance here -- it’s wrong what they do to people,” she said.

As for Sandy Reeves, still dealing with her flooded home and significant damage, her mind is likely made up.

“I’m still gonna vote for DeSantis,” she said. “There’s certain things he can do and certain things he can’t do, but you know, someone needs to tell him to address the insurance situation.”

(Updates to reflect how critics refer to the state law referred to in fourth paragraph.)

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.