Jun 26, 2024

Chicago Hunts for More Revenue as Gains from Pandemic Aid Expire

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Chicago leaders have initiated what could be a thorny discussion focused on ways to raise revenue as federal pandemic aid winds down over the next couple of years.

The city council’s new revenue subcommittee held its inaugural meeting Wednesday to study whether Chicago is taxing the right activities, the right people and at the right level as well as potential sources beyond levies. The panel held its first subject matter hearing including a presentation from first-term Mayor Brandon Johnson’s financial team.

Aldermen threw out suggestions as the administration addressed questions around ideas such as expanding taxes to services, fining big rig trucks that drive on residential streets and making the rich pay more.

“Are we still taxing the right things?” Annette Guzman, the city’s budget director, said during the hearing. “It’s incumbent upon us that we have a robust and diverse revenue structure.”

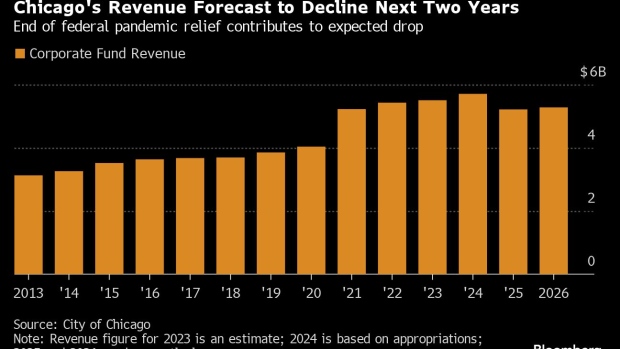

After the bump from the federal American Rescue Plan Act pandemic funding in 2021 and 2022, growth is slowing and revenue is expected to dip marginally in 2025 and 2026, according to the city’s presentation on Wednesday. Revenue for the city’s corporate fund, its main operating account, will decline from a peak this year of $5.7 billion, according the city’s forecast.

Finding new revenue that’s more equitable has been a cornerstone of Johnson’s message since his upstart campaign led him to victory over incumbent Lori Lightfoot last year. The additional dollars, however, have eluded him while old and new costs from long-term pension debt to new migrant care keep adding up.

Striking a balance to find more revenue without further burdening tax-fatigued residents and businesses will be tricky. In March, voters rejected the so-call mansion tax he championed to reduce homelessness in Chicago.

Some residents and aldermen are asking for more equitable taxes while businesses such as the hospitality industry caution that their members already face some of the highest levies in the country.

“This is a move of economic parity,” Alderman William Hall, the chairman of the subcommittee, said in an interview on Tuesday. “We need to have a revenue structure that when you walk out your door that you see your taxes are right in front of you in the city of Chicago taking care of its residents and taking care of business.”

The city needs revenue for age-old problems such as fixing roads in dilapidated neighborhoods and building up technology to attract businesses. The need for affordable housing and mental health services in long-suffering communities now also compete with resources that migrants landing in Chicago largely from Texas require.

Johnson’s administration has hired a couple of consultants to research the potential expansion of sales taxes on services and is reaching out to state lawmakers to “hopefully start a fruitful discussion” that could advance the city’s perspective, Chief Financial Officer Jill Jaworski said during the hearing Wednesday.

Sales taxes in Chicago and Illinois are focused on goods but expanding the base to a broad array of services could reduce the rate and ease burdens on lower income residents who spend a greater portion of their paychecks on food and household goods, she said.

Any changes to sales taxes require state approval.

“Over time, the amount of consumer spending on goods has continued to decrease as a percentage,” Jaworski said. “The amount on services has increased and at this point only about 30% of consumer spending is on goods, and since that’s what we are taxing we have a shrinking base.”

Alderman Brendan Reilly on Wednesday said he wants the mayor to instead look for ways to cut the budget and find efficiencies. Some aldermen said they were concerned about asking taxpayers for more money given the fiscal challenges and difficult choices the city faces ahead.

The city shed its one junk rating in late 2022. It is regularly forced to close gaps in its annual budget during many years with one-time gimmicks or sweeps of surpluses from tax-increment financing district funds that are actually intended for economic growth projects. Plus, the city also owes roughly $35 billion to its underfunded pensions, the biggest long-term weight on finances.

Alderman Bill Conway earlier this week said he wants to study ideas such as revising fees that haven’t changed in years and wants to better understand congestion pricing. Still, he said he’s cautious because of concerns that new taxes on services could drive businesses to the suburbs.

So far this year, revenue is lagging expectations.

The city has collected $934.3 million through April, 17% below the estimate in its 2024 budget, according to a monthly report. Guzman said the first four months represent only about 13% and the heaviest portion of revenue comes later in the year.

(Updates with comments from CFO starting from eleventh paragraph.)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.