Mar 7, 2022

Cathay Pacific Bleeds Millions as Staff Fear China Takeover

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- In late January, staff of Cathay Pacific Airways Ltd. were invited to an online meeting with senior management. It was supposed to be a debrief on the airline’s financial performance, but when the floor was opened to questions, the first was whether Hong Kong’s flag carrier would be taken over by its state-owned shareholder Air China Ltd.

Clearly annoyed, Cathay Chief Executive Officer Augustus Tang dismissed the notion, according to a recording heard by Bloomberg News. He called it “really sensational and hypothetical” and “grossly untrue.”

The audience of pilots, flight attendants and other employees was unconvinced. That the subject was even raised reflects the level of anxiety and distrust at the 75-year-old airline, which has gone from being a symbol of Hong Kong’s openness to one of its decline.

Made a cautionary tale for businesses that didn’t rein in their staff during 2019’s anti-China protests, Cathay has since been hammered by some of the most stringent travel curbs in the world, as Hong Kong’s government strives to toe Beijing’s isolationist line on walling out the virus.

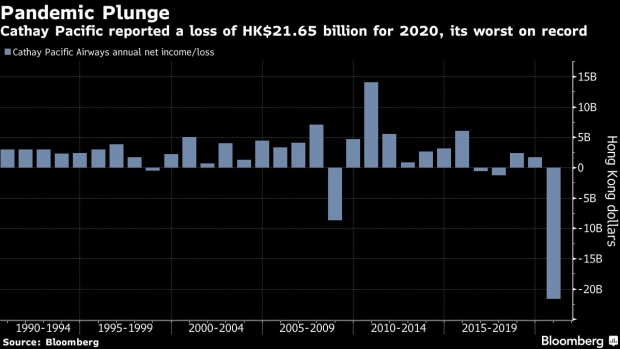

The restrictions have decimated Cathay’s passenger business, leaving it more reliant on cargo operations for income. The airline, due to report annual results on Wednesday, is flying at about 2% of 2019 capacity and is bleeding as much as HK$1.5 billion ($192 million) a month.

Cathay’s second-largest investor with a 29.99% share, Air China can’t raise its stake without bidding for the entire company, thanks to a 2006 shareholding agreement. Still, such is the level of suspicion among staff at the storied carrier -- especially when it comes to Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam’s Beijing-backed administration -- that speculation persists about the government’s plans for the airline, according to interviews with multiple current and former Cathay workers.

By far the city’s dominant airline, Cathay has long been a crucial cog in Hong Kong’s functioning as a financial center and Asian transit hub. But the sheen has come off the company, as it has Hong Kong, which is no longer regarded as the freewheeling, global metropolis it was. The protests and Covid restrictions put paid to that. People are leaving in their thousands.

Read more: Bankers Are Abandoning Hong Kong as Beijing, Covid Remake City

China’s growing influence on everything from politics to law and education sparked the 2019 demonstrations and has driven some of the exodus. One reason questions are raised about Cathay’s destiny is that it is still majority-owned by Swire Pacific Ltd., a two century-old British conglomerate with roots in the colonial era. That’s something that could still rankle with the mainland and has stoked the talk of a takeover.

No Ally

Cathay spokesman Andy Wong said there’s been no change to the airline’s shareholding structure. While it faces an “incredibly challenging environment,” Cathay has confidence in Hong Kong’s long-term status as a global aviation hub and the carrier’s place at the center of that. Swire remains a committed long-term shareholder, spokesman James Tong said. Air China didn’t respond to an email for comment.

The Hong Kong government has a 6.1% stake and two observers on the board following a HK$39 billion rescue plan in 2020 that Chairman Patrick Healy, who is also a director at Air China, said saved the airline from collapse.

Yet despite its hand in the company, Lam’s administration hasn’t been an ally for Cathay.

In addition to the Covid curbs -- which at one point saw travelers effectively banned from the U.S. and U.K., and three-week hotel quarantines the norm -- the government has publicly criticized staff and management. It’s even threatened to take legal action against Cathay after two workers broke quarantine rules and were subsequently blamed for sparking the omicron outbreak that’s become Hong Kong’s worst of the pandemic.

Speculation about the airline’s future has swirled for years, escalating in 2019 when authorities in Beijing summoned senior management after some Cathay staff took part in the protests. That led to the resignations of then CEO Rupert Hogg and Chairman John Slosar, while Swire’s chairman at the time, Merlin Swire, had to fly to Beijing for crisis talks. The airline was also criticized by protesters for ceding to Chinese demands, leaving it cornered in an unwinnable position.

The Hong Kong government defended its actions in an emailed response. It said it was committed to upholding the city’s international aviation reputation. However, it did not address concerns from Cathay staff that its actions were detrimental to the airline’s ability stay in business.

Job Squeeze

Being a pilot for Cathay is no longer regarded as the plum job it once was. Gone are the days of flying in low over the Kowloon tower blocks into Kai Tak Airport, memorialized in pictures that still dot the city’s art districts and sitting-room walls. These days, aircrew -- if they still have a job -- are sent to mandatory quarantine, separated for weeks from their families.

As part of its restructuring, which saw 5,900 jobs cut in October 2020, Cathay asked Hong Kong-based pilots to sign new contracts that involved lower pay. When the government started publicly pinning the omicron outbreak on the airline, there were reports of staff being abused in public, and their children excluded from medical clinics.

Hong Kong’s shifting political sands have made government relations more challenging. Cathay hasn’t prioritized that flank as much as it should have, said people familiar with the airline, which is looking for a new government affairs manager to “protect, promote and look after” Cathay’s interests, according to an advertisement on its LinkedIn page.

Regina Ip, a lawmaker and member of Hong Kong’s executive cabinet, said the government wants Cathay to succeed, provided it repairs relations with top officials.

“In a way, it’s a symbiotic relationship, it’s our flagship carrier, it’s the only one we have,” Ip said in an interview. “The government needs Cathay as much as Cathay needs government support.”

But with Hong Kong in the grip of Covid and showing no sign of reopening to travel any time soon, Cathay continues to face an uncertain future. Meantime, rivals like Singapore Airlines Ltd. return to the skies as other places live alongside the virus. Cathay said in January it expects a net loss of between HK$5.6 billion and HK$6.1 billion for 2021.

“We are currently not seeing any signs of significant recovery in passenger travel demand,” Cathay Chief Customer and Commercial Officer Ronald Lam said when unveiling data that showed the carrier flew just 797 passengers a day in January. “We’ve had a very difficult start to 2022.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.