Jun 27, 2024

Iran’s Election Overshadowed by Economic and Regional Turmoil

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Maryam, a 37-year-old fitness instructor in Tehran, used to put her disdain for Iranian politicians to one side for elections on the basis her vote could help to bring about change.

This year, she says she has “zero” interest.

“In every corner of this country, wherever you look, there’s nothing to be optimistic about,” she said from her home in the Iranian capital. “Prices get higher and higher by the day. On top of that, they make things more difficult with the hejab — confiscating your car, forcing you to report to the police or to courts, making you pay hefty fines.”

Maryam was referring to the Islamic head covering that’s mandatory for women in Iran. The rule was the target of widespread demonstrations in 2022 following the death in custody of Mahsa Amini, a young woman arrested for allegedly flouting strict Islamic dress codes.

Iran’s ruthless response to those protests is just one of the bones of contention going into Friday’s snap presidential election, when voters will decide a successor to Ebrahim Raisi, the hard line cleric who died in a helicopter crash last month. Other issues include the grim state of the sanctions-hit economy and the country’s role in ongoing Middle East turmoil, including the war in Gaza.

According to state-run polls, one of three men — reformist Masoud Pezeshkian, hard liner Saeed Jalili and conservative Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf — will be voted in as Iran’s next president, operating under Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran’s most senior authority. Results are expected at some point on Saturday or Sunday.

Mostafa Pourmohammadi, a cleric, completes the quartet of candidates after two others pulled out in the days before the election. If none of the four secure more than 50% of the vote, a second-round runoff will be held — possibly on July 5.

Economic Misery

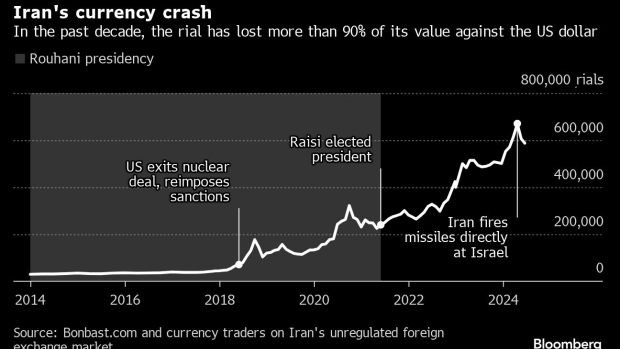

Iranians have been struggling with high inflation, a plunging currency and stagnant economic growth since the US resumed and broadened economic sanctions in 2018, after the Donald Trump administration exited a landmark deal with world powers that restricted the Islamic Republic’s nuclear activities.

The situation is compounded by high levels of corruption and chronic nepotism, something all the candidates acknowledge and pledged to address in televised debates.

Isolated from global banks and with depleted foreign-currency reserves, Iran’s next president may have to review relations with the US to improve the situation — a policy unlikely to find favor with Khamenei.

Politicians “who are pinning their hopes on those outside the borders of the country” are doomed to failure, the Supreme Leader said in a speech on Tuesday.

Iran’s economy requires massive amounts of foreign and domestic investment and a major overhaul of how it’s managed, said Bijan Khajepour, managing partner at the Vienna-based consultancy EUNEPA. Pezeshkian is the most likely of the four candidates to attempt that because he believes in trying to get US sanctions lifted, and wants to see experienced experts in government, he said.

“The economy is the top priority for the people,” Khajepour said. “They want an end to this prolonged period of economic misery.”

If Pezeshkian wins it could bring a short-term boost to the rial, as Iranians may feel more comfortable keeping capital at home, Khajepour said. In contrast, a Jalili win would mean a more hawkish stance on negotiating with the West over Iran’s atomic activities and a shift closer to Russia, China and even North Korea. Among hard liners like Jalili, the nuclear accord, which was meant to curb Iran’s program to prevent it being able to build a bomb, was never popular.

While Jalili will not generate much support with educated Iranians in urban centers, particularly Tehran, he can rely on a pious and largely working-class constituency that’s fiercely loyal to Khamenei and always votes out of a sense of religious and civic duty.

For that reason, a low turnout often works in favor of a hard line candidate, as demonstrated by the 2021 presidential election that brought Raisi into office on record low participation.

Clutching at Straws

For 36-year-old Ali, who works for a charity and runs his own retail business in central Tehran, Pezeshkian is offering enough to get him to the ballot box in pursuit of change.

“I’m going to vote for Pezeshkian,” he said by phone. “I don’t have high hopes that he will get elected or be able to do much as president, but I’m clutching at straws to prevent more devastation and chaos.”

Ali, who like Maryam didn’t want to give his full name because of the sensitivities of speaking with foreign media, has fond memories of his teenage years during the 1997-2005 reformist presidency of Mohammad Khatami.

“For the first time in many years, we have the opportunity to have another reformist president,” he said.

Iran’s electoral polls — all of which are run or approved by the state — have Pezeshkian in the lead and estimates for the turnout have increased since last week.

But the likes of Maryam — who last voted in 2017 under the reformer Hassan Rouhani — have had enough. Another fitness instructor she knows was recently forced by authorities to suspend her Instagram account because she posted instructional videos with her hair tucked under a baseball cap instead of officially approved types of hejab.

“It’s an absolute joke. How can they run an economy when they treat small businesses like this?” she said. “We always think maybe we can change things or maybe the clerics will go. But they won’t go anywhere.”

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.