Feb 10, 2022

The BOE’s $4 Billion Loss That Puts QE on Road to Fiscal Burden

, Bloomberg News

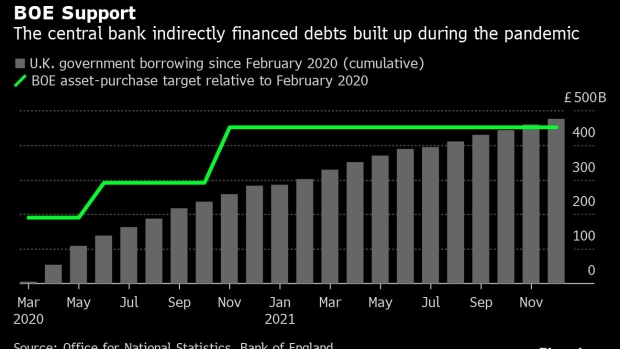

(Bloomberg) -- The Bank of England’s quantitative easing program is on course to book a 3 billion-pound ($4.1 billion) loss in the coming weeks as the central bank’s massive bond holdings start their journey from government cash cow to a drain on the public finances.

The BOE decision this month to begin unwinding its 895 billion-pound bond stockpile kicked off a process that will see gilt holdings fall by more than 200 billion pounds by the end of 2025.

The issue is that the price paid on most of those securities was well above face value, leaving the central bank in the red once they mature or are sold. Under a government indemnity with the BOE, the state must make good the difference. The shortfall for the total QE holdings amounts to about 115 billion pounds.

The QE reversal is a huge moment for a tool that’s gone from emergency measure to core policy over the past decade. It’s part of an aggressive monetary tightening by the BOE, which has already raised interest rates twice and is expected to follow with more through 2022.

So-called quantitative tightening starts in March, when 28 billion pounds of its gilt holdings will mature, and for the first time since QE was launched in 2009, bonds will run off the balance sheet. That will crystallize a 3 billion-pound loss, the difference between the nominal value of the debt and the price at which the BOE bought it.

While that shortfall will be more than covered for now by the income generated on the remaining bond holdings, the combined impact of capital losses and the higher cost of QE as interest rates rise will prove a toxic combination for Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak.

If rates evolve as markets expect, the windfall from QE for the chancellor, which had been forecast to be 11.3 billion pounds in the coming fiscal year, will soon be whittled down to nothing. In 2025 at the latest, the Treasury will start making direct cash transfers to the BOE, according to calculations by Bloomberg.

When that happens, it will bring to an end a period during which successive chancellors enjoyed profits from QE, albeit with a warning that the bill would eventually come due. The higher rates go, the greater the damage to the government.

Jagjit Chadha, director of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, said this week that the “handling of QE is an enormous problem.”

“At the moment, QE has yielded a return to the Treasury of over 100 billion pounds,” he told lawmakers on the Treasury Committee lawmakers on Monday. “As interest rates start to pick up to 1% and above, that flow will reverse.”

Chadha warned that transfers of taxpayer funds to the bank could pose a fresh risk to BOE independence, a matter which has come under increased scrutiny during the pandemic.

The BOE and the U.K. Treasury addressed the issue in correspondence last week, with BOE Governor Andrew Bailey highlighting an agreement that “reverse payments from the government were likely to be needed in the future” and “be met by the government on a timely basis.”

In response, Sunak pledged that “any potential future cash shortfalls will be met in full.” The two institutions declined to comment further.

In the 13 years QE has been running, the Treasury has received 120 billion pounds as the interest paid on the gilts is round-tripped through the BOE back to the government, minus some charges. That effectively represents a saving on payments that would otherwise have been made to the private sector.

As the gilts mature, though, capital losses on the portfolio will have to be met. Active gilt sales, which the BOE will consider once rates hit 1%, would likely worsen the impact.

The QE program has already booked losses of about 28 billion pounds on bonds that have matured since 2013, but they went largely unnoticed as the funds were reinvested and the cost was swallowed up by the proceeds from coupon payments.

Those payments will also more than cover the March shortfall. As a result, the Treasury will only forfeit income then rather than make a direct cash payment.

In 2025, however, if interest rates follow expectations, the Treasury will have to declare an annual transfer to the central bank in the budget, a payment that will likely become increasingly common as the plan is unwound. If rates rise quicker or to a higher level, that payment could come even earlier.

“Then we’re in a world in which we’re not quite sure why interest rates may not be going up. Is it because of inflation prospects or is it because we’re worried about reversing that flow of income?” Chadha said.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.