Jun 6, 2024

Sunak’s Cap on Migration Would Complicate BOE’s Inflation Fight

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s pledge to cap the number of immigrants entering the UK risks colliding with the Bank of England’s effort to keep inflation in check.

Struggling to gain traction in his bid for re-election, Sunak has promised to introduce a strict annual limit on visas issued to those seeking to come to Britain. Economists warn that those curbs could reduce the flow of workers, restraining the UK’s ability to grow without sparking a jump in wages and prices.

Such limits could play into the central bank’s decision on when to lower interest rates, which have been stuck at a 16-year high since last September. While inflationary forces are receding, BOE officials led by Governor Andrew Bailey say they’re watching wage data carefully for signs that those pressures will stick around.

“It makes the UK labor market less flexible, less efficient, less responsive,” said Jonathan Portes, a professor of economics at King’s College London. “That in turn means that the cost of reducing inflation is higher.”

Official labor market data due on June 11 may show wage growth accelerated in the three months through April after a near-10% increase in the minimum wage. It would leave pay inflation at more than 6%, well above the BOE’s comfort level. Consumer-price inflation shot up to a four-decade high of 11.1% after the pandemic ended, prompting workers to push for higher wages and companies to pay more to secure they staff they need.

Britain’s labor market remains smaller than it was before the pandemic after more than 800,000 people dropped out of the workforce. Those shortages have kept wages strong even as unemployment started to tick up.

“Tightening the immigration system will increase the pressure on UK businesses, who are struggling to fill almost 900,000 job vacancies,” said Jane Gratton, deputy director of public policy at the British Chambers of Commerce. “Immigration has a role to play in meeting urgent skills needs when firms have done everything they can to recruit and train locally.”

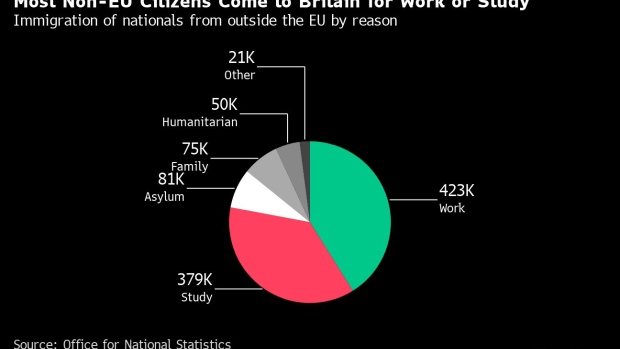

Yet for Sunak, capping immigration is a political imperative. Net migration reached 685,000 last year, down from a record of 764,000 in 2022. That’s still around historically high levels and well—above figures seen when Sunak took office. It’s also many times the “tens of thousands” promised by David Cameron when he was prime minister more than a decade ago.

Both the Conservative government and Labour opposition leader Keir Starmer have promised to cut those numbers, but pressure on Sunak has mounted with attacks from the right wing of his party. Those were highlighted this week when Brexit architect Nigel Farage announced his candidacy for a seat in Parliament representing Reform UK, which is pushing for a target of net zero migration.

Sunak has tried to associate himself with interest-rate cuts. Asked if a vote for the Tories was a vote for lower interest rates, he said: “Of course it is, because we are the party who has committed to bringing down inflation, which is a necessary condition for bringing down interest rates,” according an interview he gave to the Times newspaper.

A cap that strict could be a disaster for the economy, drying up the number of people available to work and forcing companies to bid up wages. Near record numbers of migrants have helped ease those shortages, and without them, the labor market would probably shrink, said Ashley Webb, a UK economist at Capital Economics.

Many became inactive — neither in work nor looking for a job — due to long-term sickness, to retire or for education. Hetal Mehta, head of economic research at St. James’ Place, warned that a migration cap “will heighten any perceived labor shortages and firms will have to pay more on that basis.”

Sunak has yet to announce the exact level at which he would cap the annual number of visas, which would be decided in consultation with the Migration Advisory Committee. The limit would apply to work and family visas, but would not target overseas students.

Lower net migration could hurt the public finances directly by reducing the number of workers paying tax. The UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility estimated a “low migration” scenario would increase borrowing by about £14 billion ($17.9 billion) a year by the fiscal year ending in 2029 and push up debt-to-GDP by 2.5%.

“Understanding some of the fiscal implications of this would be a key consideration for the Bank of England,” Mehta said. “The long-run effect of lower immigration would probably be higher inflation.”

To be sure, fewer people coming to the UK from overseas could reduce pressure on public health, housing, roads and schools, boosting living standards for Britons. A study by David Miles, chief forecaster at the OBR, found that a falling population means less investment is needed to maintain public services, freeing up money to boost consumption and wages.

Still, for living standards to improve, the boost in GDP per capita delivered by declining population numbers would have to offset the fall in demand. Lower net migration might also exacerbate worker shortages in areas like health and social care, which have become increasingly reliant on migrants.

Businesses and economists are calling for the government to cushion the potential blow from falling migration with measures to bring people back to work.

“There needs to be a serious debate about a pragmatic and stable employment plan that balances investment in skills and training,” said Kate Nicholls, chief executive of UKHospitality. “While we recognize the need to control migration, this debate cannot be arbitrary and divorced from economic reality.”

--With assistance from Andrew Atkinson.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.