Dec 21, 2023

RBA Expected to Trail Global Peers in Pivoting to Interest Rate Cuts

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Australia’s central bank was slow to respond to mounting inflation pressures post-pandemic and money market pricing suggests it will also trail global peers in shifting to rate cuts.

Apart from Japan, Australia is the only other developed economy where traders are uncertain whether policymakers will start lowering the key rate in the next six months. Once the Reserve Bank’s easing cycle begins, the market sees it cutting the least — with two quarter-point reductions against as many as six each for the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank.

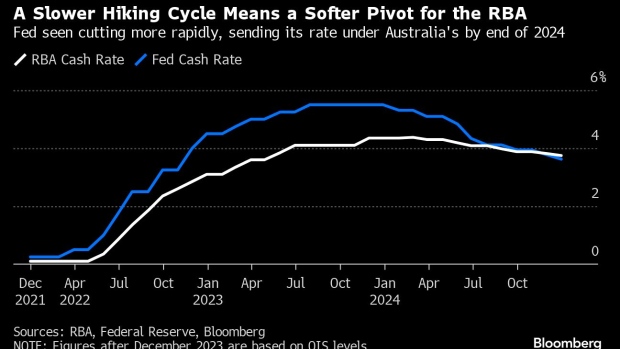

The RBA’s policy rate is 1 percentage point lower than the Fed’s, underscoring its measured pace of tightening, even as Australia’s inflation remains above that of the US and UK. These differences help explain why Governor Michele Bullock has stuck with a hawkish tone and why money markets expect the RBA to move cautiously on the way down.

“The RBA has not hiked as much as the other central banks have, which means a shallower cut and probably a cut that starts later makes more sense,” said Shreya Sodhani, a Singapore-based economist at Barclays Plc. “Bullock also to me seems more hawkish than Governor Philip Lowe was.”

The RBA started tightening later than peers, yet shifted to smaller, quarter-point moves earlier. Now, as global disinflation trends beg the question whether Australia will again lag its peers, what’s clear is that the RBA will stay hawkish until it sees credible signs that inflation is moving back to target.

This month US policymakers forecast rate cuts for 2024, prompting traders to bet that the Fed’s target rate will drop below the RBA’s cash rate by the end of next year.

The RBA, in the minutes of its Dec. 5 meeting, highlighted risks that inflation will hold above the 2%-3% target for longer than anticipated. Its current forecasts show price gains hitting the top end of the band only at the end of 2025. In the US, inflation is seen by a Bloomberg survey at 2.6% next year.

Australian inflation is proving stickier, with Bullock saying last month that the challenge is “increasingly homegrown and demand-driven,” and that bringing the print below 3% from about 5.5% now is likely to be a drawn out process.

The RBA isn’t likely to cut rates until late 2024, possibly in September, according to Westpac Banking Corp.’s Chief Economist Luci Ellis. That will likely see the Australian dollar strengthen to 70 US cents next year, from around 67.5 cents now, partly because local borrowing costs will come down more slowly than for the US, said Ellis, previously an assistant governor at the RBA.

Record population growth is also adding to price pressures while boosting the economy’s resilience and shielding it from recession.

Population surged by 2.5% in the year through September, fueled by net migration of more than half a million people, compared with a pre-pandemic average growth of 1.5%.

“With issues like Israel, Gaza, the Red Sea, there’s obviously still some potential inflationary pressures globally and so that’s something we are quite wary of,” said Anna Shelley, chief investment officer at AMP Ltd. “We might see one cut, I guess maybe two by the end of next year, but more likely one.”

The RBA doesn’t meet next month. In February, it begins a new system that includes two-day meetings, the rate statement being signed by the board rather than just the governor and Bullock holding a press conference.

The quarterly update of economic forecasts will also be released simultaneously with the rate statement, instead of three days later.

--With assistance from Amy Bainbridge.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.