Jun 14, 2024

ECB Officials See No Cause for Alarm Over France’s Market Turmoil

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- European Central Bank officials see no cause for alarm in the market turbulence that has engulfed France in the past few days, according to people with knowledge of the matter.

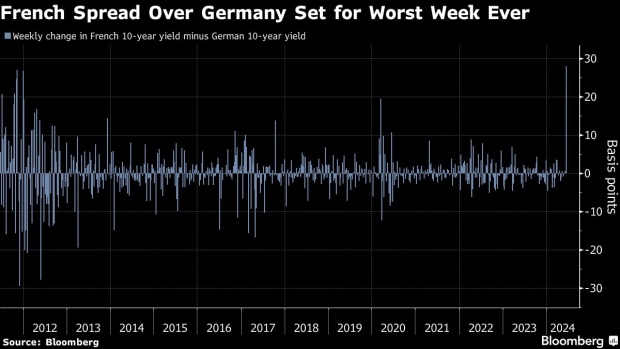

Turmoil that put the spread between French and German 10-year bond yields on track for its biggest weekly jump on record and wiped $200 billion off the value of the country’s stocks remains contained in the eyes of policymakers and no talks on crisis tools have even been considered as of Friday, said the people, who asked not to be identified because any deliberations are private.

A spokesperson for the ECB declined to comment.

The market gyrations erupted in the wake of President Emmanuel Macron’s call for a snap parliamentary vote after his party’s defeat to Marine Le Pen’s National Rally in the European elections.

The market reaction hasn’t been limited to France, with bond spreads of other euro-area members such as Italy also widening. For the ECB, any prospect of contagion could evoke memories of the region’s sovereign debt crisis of the previous decade.

The ECB would face a bind if turmoil were to spiral out of control and force them to consider using one of their crisis tools. The size of the euro zone’s second-biggest economy could require intervention on a scale never attempted, and any action would be conditional on the compliance of an incoming administration.

The last time officials had to resort to emergency measures was only two years ago, when the prospect that policymakers were about to start raising interest rates caused Italian yields to soar.

Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire warned this week that a “debt crisis is possible” if Le Pen’s nationalist party were to win, and also cautioned that victory for a newly formed left-wing alliance could lead to France’s exit from the European Union. Bank of France Governor Francois Villeroy de Galhau, meanwhile, said the next government must quickly clarify its economic policy.

While the ECB has long been used to turmoil because of its experience of the sovereign debt crisis of the previous decade, its need for emergency action has become rarer.

In June 2022, policymakers were very fast to act on Italy’s bond crisis.

Within days, President Christine Lagarde had convened an crisis meeting that she conducted from the basement of a London hotel to secure the agreement on a new crisis tool aimed at preventing fragmentation in the euro zone — the so-called Transmission Protection Instrument, TPI.

The creation of that instrument and the existence of others may be one element of reassurance that allows policymakers to stay sanguine and keep watching from the sidelines.

But the recent turmoil led to increased discussions among investors and analysts about the conditions for possible activation of TPI, even if many are highly skeptical.

“If severe French fiscal mistakes trigger a blowout in yield spreads, the ECB could be reluctant to immediately use this instrument,” Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Berenberg Bank, wrote this week in a note, arguing that it would be “highly controversial” within the ECB and in European politics.

Executive Board member Isabel Schnabel, who is in charge of market operations at the ECB, said in a speech about fiscal and monetary policy in early June — before the EU election and Macron’s shock announcement — that TPI “is only used in countries that pursue sound and sustainable fiscal and macroeconomic policies.”

She highlighted that the central bank “cannot counter persistent tensions that are due to country fundamentals” with the instrument.

Asked about the situation in France, Lagarde told reporters on Friday that she didn’t want to comment on domestic political situations.

“I will simply say that it is the duty of the European Central Bank to deliver on its mandate and to keep inflation under control and back to target that this is what we’ll be doing,” she said in Dubrovnik, Croatia.

--With assistance from Jana Randow, Jasmina Kuzmanovic, Alessandra Migliaccio and William Horobin.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.