May 15, 2024

Deadly US Oil Blast Exposes Risks of Pushing Profits Over Safety

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The explosion that rocked Marathon Petroleum Corp.’s Galveston Bay oil refinery one year ago trapped Rigoberto Guillen 75 feet in the air. Stranded on a metal platform, he and a colleague crouched low as black smoke engulfed them. “I couldn’t see my coworker,” Guillen said. “I couldn’t even see the sun.”

When the men were finally able to scramble down three flights of cage ladders — the soles of their boots liquefying on the hot metal — they emerged with burns on their wrists, hands, faces and ears. “I saw my coworker’s nose basically melt off,” said Guillen.

They were relatively lucky. Scott Higgins, a 55-year-old machinist, burned to death. It was the Texas refinery’s worst tragedy since 2005, when an explosion killed 15 and injured scores more.

The source of the blast was a leaking pump that the company had identified as needing maintenance, according to an internal Marathon investigation shown to refinery workers and described to Bloomberg. But the work, along with other vital upkeep, got pushed back amid the company’s drive to maximize production.

Marathon, the largest fuel producer in the US, had for two years been deferring maintenance at its plants, in part to take advantage of historically high refining margins. They weren’t alone. When gasoline consumption rebounded after the worst of the pandemic, many refiners postponed maintenance as profits to turn oil into fuel shot to a record high.

“When margins are high, there’s a lot of financial pressure not to shut the refinery down for maintenance,” said Daniel Horowitz, a former managing director at the US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board. “That can lead to accidents.”

Marathon, which is facing litigation related to the blast, declined to comment on the matter. But a spokesman said in a statement: “We are deeply saddened by the loss of our colleagues,” adding, “We operate our facilities with the highest commitment to the safety and health of our workers and the community.”

What happened at Galveston Bay highlights a challenge faced by fuelmakers across the country. The US refining system — already stretched to the limit after the pandemic shuttered more than 1 million barrels a day of capacity — is scrambling to meet ever-higher fuel demand with an aging fleet of plants that require costly and regular overhauls. Maximizing fuel production when margins are high is common industry practice, with refiners trying to ensure worker safety while maintaining their fiscal responsibility to their shareholders.

They don’t always strike that balance. Deferred maintenance is a root cause of refinery deaths in the US, according to a 2006 report from insurer Swiss Re. But while the pattern is well-documented, US oversight is floundering: Government data on injuries and deaths is patchy, and penalties for violating safety regulations often amount to little more than a rounding error in company balance sheets.

In the lead-up to the Galveston Bay explosion, Marathon deferred a type of maintenance that, according to the company’s internal investigation, would have helped to catch a crack on a pump near a gasoline-making unit. Instead, the pump continued running — and eventually leaking — highly flammable chemicals. A nearby sprinkler system was also broken, an OSHA inspection showed.

Marathon, in a statement, characterized its internal investigation as “part of our comprehensive process for continuously improving personal and process safety across our operations.”

“We strive to provide a work environment where our employees and teams are empowered to take whatever action is necessary to achieve our goal of an injury-free workplace,” the company said.

Yet days before the May 15 explosion last year, the company’s then-Chief Financial Officer Maryann T. Mannen characterized delayed repairs as “good decisions” that enabled Marathon to meet rising fuel demand after the pandemic. Indeed, Marathon’s refining profits, as well as its annual net income, were the highest on record the year before the explosion.

Legacy of Deadly Cost-Cutting

To be sure, the Galveston Bay refinery had a deadly record well before Marathon purchased the plant in 2013. It was also the site of the 2005 Texas City explosion that killed 15 workers and injured 180. The cause of that blast, according to a CSB investigation, was cost-cutting by then-owner BP Plc.

The BP explosion, known as one of the worst refinery disasters in US history, became the first in a string of major incidents that forever marred the company’s safety and environmental record. Just months after the Texas City fire, while BP was still contending with the fallout, company pipelines spilled more than 5,000 barrels of crude in Alaska. In 2010, an explosion at the offshore Deepwater Horizon drilling rig killed 11. The company eventually sold the Texas City refinery to Marathon – which renamed it Galveston Bay – to help cover the costs of the Deepwater Horizon disaster.

After Marathon acquired the refinery, the company made strides in improving safety, according to current and former workers. But after the pandemic decimated fuel demand, the cost-cutting began again. Post-pandemic, Marathon eliminated dozens of refinery operator positions and combined processing units to consolidate supervision, according to people familiar with the matter who asked not to be named for fear of retribution. The gasoline-making ultraformer that blew up on May 15, 2023, was one such unit, said the people. Before 2021, the ultraformer was monitored by a single operator. After that, it was combined with two other units, meaning a single operator had to manage all three simultaneously.

The cutbacks came at a time when workers were already leaving the industry at a faster-than-usual pace according to Faisal Khan, director of the Mary Kay O’Connor Process Safety Center at Texas A&M. Many senior operators retired early in 2020, and the industry is struggling to replace them with younger workers. Workforce shortages, along with deferred maintenance, are the top two risk factors for deadly accidents, he added.

To fill the gap, companies are increasingly relying on third-party contractors such as Guillen. Contractors are cheaper than employees — they’re usually not unionized and they aren’t full-time. But they do some of the most dangerous work in the plants.

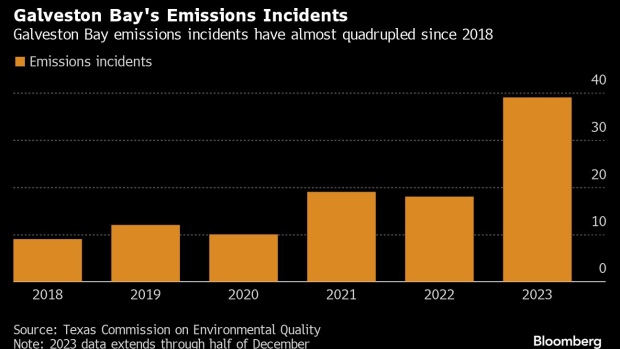

Meanwhile, the Galveston Bay plant has recorded more emissions events than any other Texas refinery last year, according to Texas Commission on Environmental Quality data compiled by Bloomberg. Those are often the result of unit breakdowns that can lead to unsafe conditions for workers.

“Every time you have a breakdown, eventually, it’s going to cause a fatality,” said Norman Lieberman, an engineering consultant who worked at Galveston Bay in the 1970s.

Failing Oversight

Deaths in the refining sector are relatively rare compared with professions like logging. But the data are deceiving, according to Jordan Barab, former deputy assistant director of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, called OSHA, under the Obama administration, and a vocal critic of the oil industry.

Bureau of Labor Statistics data, for example, show zero refinery deaths for 2005, although 15 workers died in the Texas City explosion that year. OSHA doesn’t keep refinery-specific injury and fatality statistics, and the data it does collect is often incomplete. In order to find those 15 fatalities in the OSHA database, one must know which contractor employed each worker, and under which regional OSHA office the reports were filed.

Enforcement is an issue, too. OSHA’s refinery safety rules were written in 1992 and haven’t kept up with changes to plant operations, said Mini Kapoor, a partner at Haynes & Boone who’s an expert on OSHA. And while the agency hired more inspectors and issued new directives for the industry under President Barack Obama, some of those changes were reversed under President Donald Trump.

Even when plants are found in violation of the rules, the fines levied often do little to change how companies operate.

Marathon’s Galveston Bay was among the most heavily fined refineries by OSHA last year. For last year’s deadly fire, OSHA initially fined the refinery $62,500 but after Marathon disputed the penalties, OSHA withdrew two of four citations, along with half the fines, according to documents obtained by Bloomberg through a Freedom of Information Act request. Before that, the plant hadn’t paid a fine since 2018.

OSHA declined to comment.

No Choice But to Go Back

It’s only through a fluke that Guillen and his colleagues are able to sue Marathon for their injuries.

Marathon, like most Texas refiners, asks contractors to sign onto an owner-controlled insurance program, called an OCIP, which ties the contractor’s insurance to the refinery’s workers’ compensation program. Under Texas law, workers’ comp precludes litigation, except in certain extreme circumstances. So contractors under OCIP can’t sue even if they’ve been gravely injured.

The system “severely limits the rights of contractors to pursue a claim against the property owner even if it’s entirely the property owner’s fault,” said Muhammad Aziz, a lawyer representing Guillen and other workers injured in last year’s blast.

But Guillen’s contract company, Mistras Group, hadn’t yet signed an OCIP with Galveston Bay when the fire occurred. Guillen and five other injured coworkers will seek more than $1 million each in damages.

Three months after the fire, Marathon’s Mannen acknowledged the event in an earnings call. “An incident that occurred at one of the refinery’s catalytic reformers,” she said, “resulted in approximately 2.5 million barrels of crude throughput reduction and an approximate 1% reduction to capture.” She did not mention Higgins’ death, or the injured workers.

Marathon’s margins that year fell from a record high, but only slightly. This year, margins have remained elevated.

Guillen is still not fully healed. Aside from the burns, he says he has chronic back pain and a throbbing in his ears. He also has nightmares, although they’ve gotten better. “I used to try to go to sleep and close my eyes and all I could see was red around,” he said.

But he’s still planning to return to refinery work. Shortly after the fire, he had a baby, and the bills are piling up. “I feel like I have no choice but to go back,” he said. “But, honestly, I’m very frightened.”

--With assistance from Mia Gindis and Lucia Kassai.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.