Dec 18, 2022

Powell Puts US Pay Hikes at Heart of Fed’s 2023 Inflation Fight

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has a new North Star to guide his fight against inflation, and it will put American paychecks at the heart of monetary policy next year.

Powell says he’s looking at a price-gauge that covers everything from health care and haircuts to a night in a roadside motel. Because wages are an especially big cost for those service industries, “the labor market holds the key to understanding inflation in this category,” he told the Brookings Institution in November, in his final set-piece speech before the Fed’s latest interest-rate hike.

In his press conference after that decision on Wednesday, Powell returned to the theme. Right now, he said, wages are growing “well above what would be consistent with 2% inflation.”

The pivotal question for Fed officials is whether the climb in US pay over the past 18 months or so is a one-time bump — as companies adjust to scarce labor supply, and a realization that their workforce was under-compensated — or a pernicious feedback loop in which prices and wages drive each other up.

Fear, Not Fact

The signs are that they’re not willing to take any chances, which means Powell’s new lodestar points toward tighter policy. Forecasts the Fed released last week suggest a benchmark rate of 5.1% for next year, a higher-than-expected number that set off a stock-market rout. Several Fed officials were even more hawkish than that.

“The wage-price spiral is a fear, not a fact,” says Derek Tang, an economist at LH Meyer in Washington. “Real wages are most certainly not in an upward spiral.” But clearly, he says, concern about lasting labor shortages and the implication for prices has “filtered up to Powell.”

The US labor market is especially tough to read right now because businesses are still sorting out the massive disruptions caused by the pandemic.

Unemployment soared to nearly 15% in April 2020, and then rapidly recovered. The rate today is a historically low 3.7%. But as the dust settles, growth in the US labor force appears to have stalled out below the pre-pandemic trend – for a variety of reasons, from the spate of early retirements and lasting symptoms of Covid-19, to the scarcity of child and elder care, and lower immigration.

The labor shortage gave employees more bargaining power, and pushed companies to raise pay as competition for hiring increased. In most cases, workers were barely keeping up with the soaring cost of living, not getting ahead of it. Total compensation costs for employers in the 12 months through September were up 5%, versus 3.7% a year earlier – but in both periods, real pay (after adjustment for inflation) decreased.

From Goods to Services

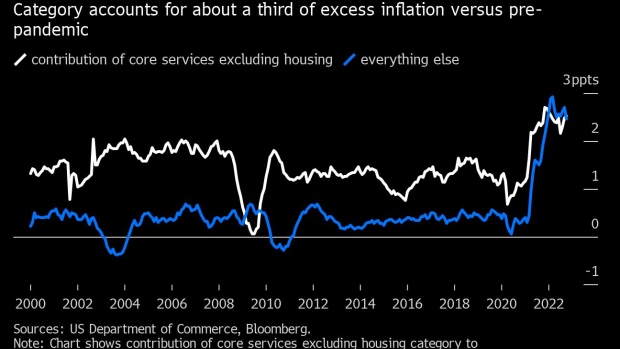

There’s a reason why Powell’s new favored inflation metric – core services excluding housing, to give it the full wonkish title – is intimately linked to the wages debate.

The Covid-era price spike showed up initially in consumer goods: they were in short supply, thanks to delivery disruptions — and in massive demand among Americans stuck at home with extra cash on hand.

As the goods crunch eased, services took over as an inflation driver. The biggest item in that category is housing, which is counted as a service in official price measures – but that’s a sector with dynamics all of its own. And among the other services, the ones the Fed is now eyeing closely, wages typically account for a larger share of costs than in other industries.

One way the US labor crunch could work itself out is for a decent chunk of the missing workers to come back. But Fed officials are in no mood to wait and see if that happens, with inflation running at three times their target.

The Fed’s latest forecasts point toward cooling the economy with even higher borrowing costs, which slows the pace of hiring and increases unemployment.

“Wage growth has been very high because labor demand has been really strong relative to available supply,” New York Fed President John Williams said during a Bloomberg Television interview on Friday. “As labor demand and supply get in better balance, the wage gains will be more consistent with longer trends and our 2% goal.”

‘Maybe They’re Right’

Williams said he doesn’t see evidence of “a wage-price spiral of the kind that we saw in the 70s.” A recent historical study by the International Monetary Fund suggests that such episodes are rare.

Still, US central bankers are determined to preclude even the possibility – and judging by their own forecasts, it will be touch-and-go as to whether they can rebalance the labor market like they want to without triggering a recession.

Fed officials expect growth to slow to a crawl of 0.5% next year, while unemployment rises almost a percentage point to 4.6% — which likely means more than 1 million Americans would lose their jobs. Even with this pain, inflation proves surprisingly sticky, only gradually slowing back to 2% by 2025.

That’s probably due to the lagged effect of falling housing costs on price indices, says Beth Ann Bovino, chief US economist at S&P Global Ratings.

“They are forecasting a soft landing, maybe they are right, maybe they can pull it off,” Bovino says. “The odds are against them.” She estimates that unemployment could rise to 5.6% next year.

‘It’s Just Ingrained’

As for the non-housing services that Powell has been highlighting, Omair Sharif — the founder of Inflation Insights LLC — sees plenty of evidence that wage growth hasn’t been the primary driver of inflation there.

Prices in that category were mainly driven by increases in transportation and medical care in the first half of the year, which have now reversed, he says. There were a variety of causes, from a sudden surge in the demand for travel to quirks in how health insurance costs are calculated.

Wages weren’t a big part of the story, Sharif says. “It’s just ingrained in everybody’s minds somehow that this is how things work.”

--With assistance from Steve Matthews and Matthew Boesler.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.