Apr 28, 2022

Dismal U.S. GDP report raises the odds of recession this year: Gary Shilling

Monetary policy is not synched up with global growth: Strategist

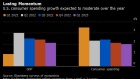

The weakness in the economy spawned in part by the liquidation of bloated inventories has only just begun. The Commerce Department’s preliminary estimate of first-quarter growth Thursday showed that gross domestic product unexpectedly shrank at an annualized rate of 1.4 per cent. Of that, 0.84 percentage point was due to a reduction in business holdings of goods.

None of this should be a surprise. As far back as December, there were signs that a build-up of excess inventories in the last half of 2021 would lead to a cut in production and orders after American businesses stockpiled goods in anticipation of robust holiday sales that ended up being rather tepid. Of the 2.3 per cent growth in the third quarter of 2021, 2.2 percentage points was due to inventory-building and 5.3 percentage points of the fourth quarter’s 6.9 per cent gain.

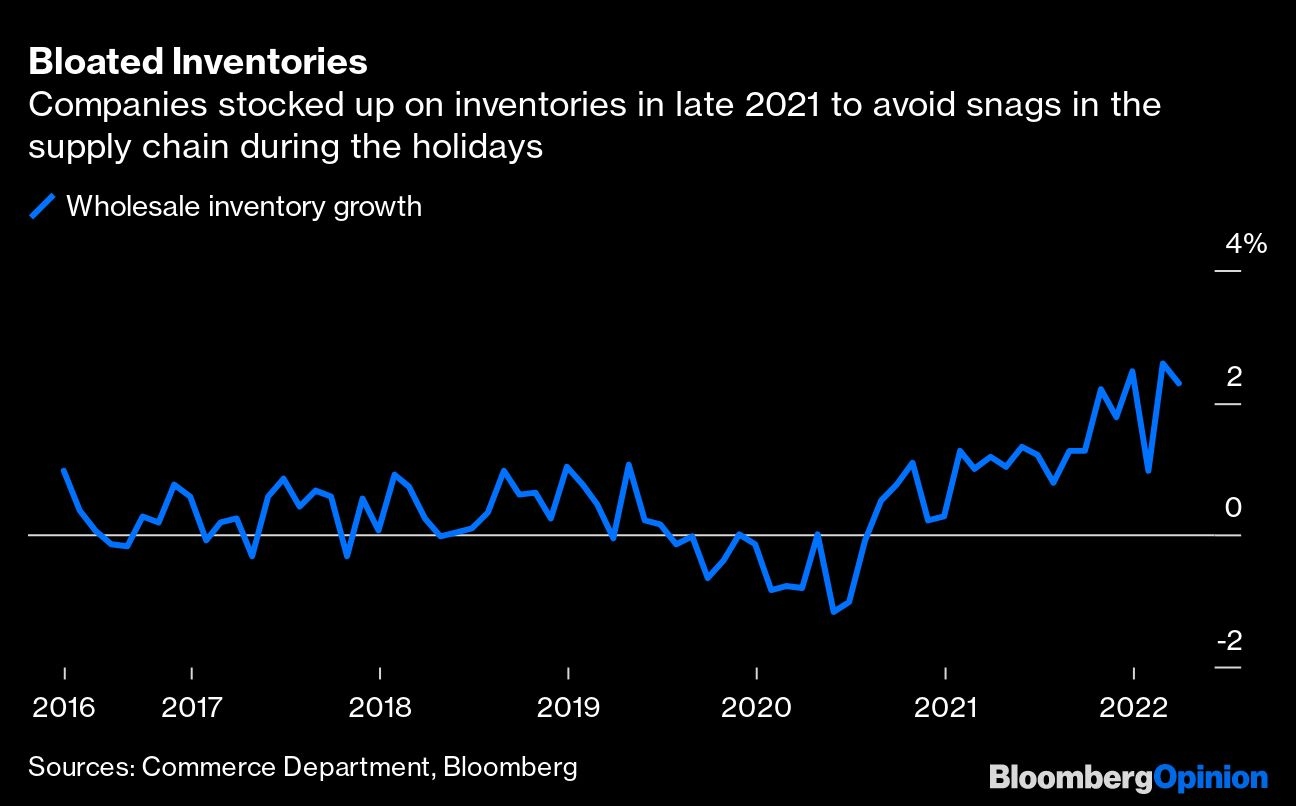

But consumers held back. Real personal consumption expenditures, which accounts for 71 per cent of total GDP, rose just 1.3 per cent in the third quarter and 1.8 per cent in the fourth. And followed by only a 1.8 per cent rise in the first quarter, there’s still lots of inventory yet to be unloaded. Real retail sales fell 0.7 per cent in March from February and consumer confidence in the future plunged 28 per cent in April from a year earlier, according to the University of Michigan’s sentiment survey.

Supply of goods will increase even as demand weakens. Some 60 ships with imports from Asia are waiting to be unloaded at the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, according to the Marine Exchange of Southern California. Those “floating inventory” vessels are down from the January peak of 109, but are still about triple the earlier norm. Also, there are hidden inventories in the guise of partially-built vehicles that will hit the market when the computer chips needed to complete them arrive.

Households also hold excess inventories. While at home during the pandemic, they bought lots of exercise equipment, televisions, computer games and kitchen appliances. That pushed up spending on durable goods 18 per cent last year. It will be years before those goods wear out. Meanwhile, look for profit-killing markdowns as businesses work off excess inventories.

Further declines in economic activity will reduce inflationary pressures as will the easing of supply-chain bottlenecks and waning frictions from reopening the economy. Also, economic weakness will probably retard the Federal Reserve’s credit-tightening campaign. Nevertheless, the central bank has been behind the inflation curve and will no doubt continue to raise interest rates and shrink its portfolio of bonds until it sees the whites of the recession’s eyes.

Decades ago, business cycles were largely inventory cycles. But inventories only exist in goods since services are consumed as produced. Now, consumer services are 61 per cent of consumer spending, up from 39 per cent in 1947, while goods purchases have dropped from 61 per cent of the total to 39 per cent. Nevertheless, inventory cycles will exist and the current one will probably speed up and intensify the business downturn I’ve been predicting to start this year.