Mar 29, 2024

Hungry Wolves Threaten Europe’s Climate Agenda

, Bloomberg News

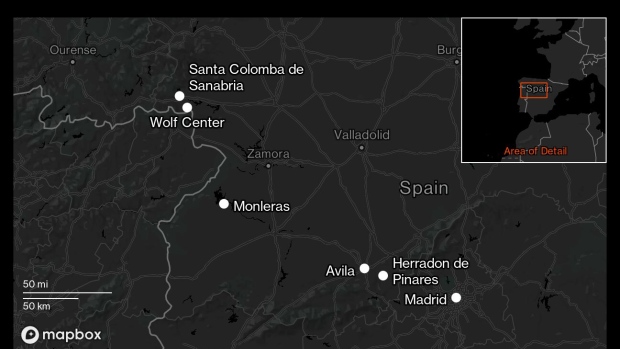

(Bloomberg) -- Juan Manuel Berguio’s cows suffered 25 wolf attacks that decimated the herd he breeds on the green hills outside the medieval city of Ávila, in central Spain. That was in 2019. Since then, he’s tried everything to keep them away, from GPS trackers to mastiff dogs, trail cameras to special fences. But he says he’s still losing animals.

“Wolves jump over walls and fences without even touching them, and they’re not scared of anything,” says Berguio as he braves the freezing rain on a February afternoon to guide his cows across the fields, calling each by name. “Over here we’re seeing attacks on a daily basis.”

Wolves attacked at least 65,500 farm animals across Europe last year. Wolf incidents are a growing phenomenon that European Union authorities attribute to the population increasing and packs moving into farming areas.

The EU’s strict protection of wolves dates back to at least 1992, but more recently the bloc has embedded biodiversity restoration into its 1 trillion-euro bid to make the continent climate neutral by 2050. Top predators are a key part of the bloc’s 115 billion-euro biodiversity strategy, because their presence ensures the health of the whole food chain; healthy ecosystems will help shield the region from the impacts of climate change.

“All of us here in this room like a world with lions, tigers, pumas and jaguars,” Humberto Delgado Rosa, the commission’s director for biodiversity, told an EU parliament committee in February. “What message would we be giving to the world if we could not cope with our own large carnivores?”

Thanks to the EU’s protection, within a few decades, wolves have gone from being considered vermin—hunted, poisoned and exterminated—to falling under the strictest protection for endangered species, their numbers recovering and packs expanding. While that change has been largely considered positive by biodiversity champions, many farmers say the protections have gone too far. That controversy is now turning into a political issue. Many farmers, and some politicians, want to change EU policy to make it easier to shoot wolves.

The rise in attacks by wolves has helped fuel the largest agriculture protests in years, with farmers already furious at rising costs and more bureaucracy. In recent weeks, angry farmers blocked roads in every major European capital with tractors, sheep and cows.

“Politicians say they’re defending rural areas and it’s all a lie,” says Berguio. His province, Ávila, has become a hotspot for wolf attacks: 1,400 were registered there last year.

But the incident that changed it all and made wolf control more prominent within EU policy happened far from there. In September 2022, a wolf known as GW950m sneaked into a farm in Germany’s Lower Saxony and killed Dolly, a brown pony with a distinct white mark on its snout that belonged to Ursula von der Leyen, president of the EU Commission, the bloc’s executive body.

After that, von der Leyen became personally involved, issuing statements and sending letters to members of the conservative European People’s Party she belongs to. A year later, the commission released a 100-page report on the state of the wolf in Europe and formally proposed lowering its protection status in December. That would allow countries with a lot of wolves to issue hunting quotas.

“The concentration of wolf packs in some European regions has become a real danger especially for livestock,” von der Leyen said then. “To manage critical wolf concentrations more actively, local authorities have been asking for more flexibility—the European level should facilitate this.”A spokesperson for the commission called the EU’s protection of wolves “a conservation success.” But, says the spokesperson, “this expansion has however led to increasing conflicts with human activities, notably concerning livestock damages, with strong pressure on specific areas and regions. This changing reality on the ground now justifies an adaptation of the legal protection status.”

Next, the commission wants EU member states to push for a change of the Bern Convention, the treaty that regulates wildlife conservation in the broader European region. That would lead to the wolf being considered “protected”—as opposed to the current “strictly protected”—and make it easier for countries with healthy populations to allow for hunting. The timing has led critics to say the commission has the June EU parliament elections in its sights.

The conservative European People’s Party is expected to win the most seats in June. Von der Leyen is a frontrunner, and a victory would give her a mandate at the helm of the commission. Polls show the European Greens losing seats and far-right parties winning them, raising fears that the EU Parliament could slow climate action in the continent during this crucial decade.

European conservatives are using wolves as a “campaign tool” to mobilize the electorate against green policies, says Thomas Waitz, a member of the EU parliament with the Greens. “The whole debate around wolves has been a very populistic one,” says Waitz, who lives in Austria. “It very much builds on sentiments, ancient fears and popular culture storytelling going back to the Grimm Brothers’ fairy tales.”

“It’s in the interest of conservatives to go to farmers and say they’ve lowered the protection status of the wolf,” says Sergiy Moroz, a policy manager at the European Environmental Bureau, which represents environmental organizations in Brussels. “But hunting is a false solution and the science around that hasn’t changed—what’s changed is that elections are approaching.”

Alonso Álvarez de Toledo y Urquijo opens the white wooden doors of his country palace on 270 hectares (670 acres) with the courtly gesture of someone who enjoys protocol. The 12th Marquess of Valdueza, now 84, used to lead the transhumance of his distinctive Avileña black cows on horseback, and he’s eager to show off souvenirs of his family’s long legacy of farming and hunting. The stone walls of his giant sitting room are lined with hundreds of hunting trophies: the stuffed heads of three lynx, two wolves and a deer leg. All were killed by his grandfather back when that was encouraged by the government. He proudly points to oil paintings of his ancestors, a Spanish noble dynasty going back more than five centuries.

There’s more to hunting than money and species management, says Álvarez de Toledo as he walks through the rooms.

“Hunting is not a sport, it's something that runs very deep inside me, because from the dawn of time men have hunted to survive,” he says. “Today it’s different, of course. Defending hunting also means defending the conservation of nature and species.”

Hunters are the most interested in preserving healthy ecosystems, he argues. Killing dozens of wolves on a single drive as was customary decades ago makes no sense because it will make game extinct over the long term.

Back when it was legal, wolf hunting permits started at around 10,000 euros ($10,838). That, plus the accommodation and food costs paid by large hunting parties, used to be an essential source of income for tiny villages. It was a way to keep Europe’s rural economies going in the face of an aging population.

“Our farmers are abandoning pastoralism and this leads to a big loss of biodiversity,” says Herbert Dorfmann, a conservative member of the EU parliament hailing from the Italian Alps, another hotspot for wolf attacks. “There needs to be a balance—at the moment the wolf's protection is at level 100 and the sheep’s protection is at zero.”

Europe needs its ranchers and shepherds. Extensive grazing can lower the huge carbon footprint of beef. Animals roaming freely across mountains need significantly less feed than those raised in farms, resulting in lower planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions. They also keep forests clean of underbrush and help prevent forest fires. But the extensive grazing makes farm animals more vulnerable to wolves, and farmers think allowing for some hunting would allow them to continue this practice.

At the moment, EU rules only allow for the hunting of individual animals proven to be very harmful to livestock. Many countries require a court order, making the process lengthy and bureaucratic. But wolves are intelligent predators that travel across huge areas of terrain, with some known to move across the entire continent. That makes catching them a difficult task.

In the case of wolf GW950m, a local court issued a hunting permit only after DNA analysis proved it hadn't just killed von der Leyen’s pony, but also at least 12 other sheep and cows in the area. The authorization expired in January before hunters could find it. The wolf remains alive.

Lowering the animal’s protection status would make it easier for farmers to kill wolves that repeatedly attack livestock, says Torbjörn Larsson, president of the Brussels-based European Federation for Hunting and Conservation. That would help locals feel directly involved in dealing with the threat, as opposed to seeing solutions as something imposed by outsiders.

“Conservation is not a problem now,” Larsson says. “But if nothing happens, if this process doesn’t take a step forward, tensions and conflict are only going to increase.”

There’s another solution that doesn’t involve more hunting, say environmentalists, Green members of the EU parliament, the Spanish central government and even some ranchers. The EU is already compensating cattle ranchers for every animal killed by a wolf, with 18.7 million euros handed out in 2022, and gives out financial aid to invest in measures to prevent attacks.

These funds are necessary because the fences and mastiff dogs that keep wolves away have been abandoned where the predators went extinct. Reintroducing them again is costly and difficult for ranchers struggling to make ends meet. While these solutions are effective for sheep farmers because sheep tend to stay together in close groups, they don’t work as well for cows, which roam the fields in small groups or on their own.

“People got used to the absence of wolves and going back to coexistence is very difficult,” says Teresa Ribera, Spain’s Minister for the Environmental Transition.

In Spain’s Castilla y León region, about 80% of wolves live in a small area north of the Douro river. The wolves never disappeared, but only 20% of attacks are registered there. The much larger area south of the Douro contains just 20% of the wolf population and registers about 80% of the attacks.

“It is horrible and quite emotional when there is a loss of a dog, pony or cow,” Ribera says, adding that authorities need better information before making any moves. “We need data, we cannot take an emotional decision.”

Existing reports don’t justify a change in the predator’s protection status, says Carolina Martín, a biologist and an environmental activist with Ecologistas en Acción based in the small hamlet of Monleras, in Castilla y León. Besides, conservation goes beyond numbers, she says. The presence of genetic illnesses is one sign that the species remains vulnerable. Trail cameras have captured images of wolves with mange, a skin disease.

“That’s an indicator that the conservation status is not positive,” Martín says. “Even under strict protection wolves are under a lot of strain, including human pressure on their natural habitat and illegal hunting.”

An outspoken critic of wolf-hunting, Martín prefers to talk in the intimacy of her home rather than the town’s single bar. She walks a tightrope between her activism and getting along with Monleras’ 200 inhabitants. Many of her neighbors disagree with her on the issue and call her ‘the She-Wolf’ behind her back. She says she likes the nickname.

Over the years she’s become more cautious. In 2021, just after the Spanish government forbade wolf hunting in the few areas where it was still allowed, two neighbors brought dead sheep to her door, entered her home, dragged her outside and forced her to look at the carcasses. After that intrusion, she limited her media appearances and posts on social media.

North of the river Douro and still within Castilla y León, a small enclave offers a glimpse of what coexistence between wolves, humans and livestock looks like. In Santa Colomba de Sanabria, home to 60 people, Alberto Fernández keeps a flock of about 700 sheep. Over the past 12 years he lost only ten animals in a single attack, an impressive record for someone working right by the Sierra de la Culebra mountain range, an area with one of the highest wolf densities in Europe.

It’s become a popular wolf-watching destination. Even before hunting was banned, eco-tourists brought in more income than hunters, according to a 2012 study. A nearby state-owned Iberian Wolf Center, home to 14 wolves in large enclosures, has received over 240,000 visitors since 2015.

Still, shepherding in wolf territory is hard work, Fernández says. All his fields, which qualify as extensive grazing territory under EU rules, are protected by electrified fences and eight giant mastiff dogs. Every night during winter, Fernández and his wife take the herd to a warehouse.

“Of course it’s tough,” he says as he drives his giant off-road truck on a cold, moonlit night. “Even more so when I think about shepherds further south who don’t need to do all this because they don’t have wolves.”

He steers the vehicle past old oak trees and muddy fields until he finds the flock. The sheep and he mastiffs wiggle their tails when Fernández and his wife open the gate, helping the dogs guide the sheep out.

The hills around them are pitch black but the sheep seem calm; the dogs, the humans and the humming engine keep them safe. Only once has Fernández seen the silhouette of a wolf sniffing the flock—and immediately there was a mastiff chasing it.

Feeding the dogs costs Fernández about 12 euros per day, but he receives some EU funding that partly covers the expense. People like him should be compensated further, he says. Traditional shepherds help keep forests and mountains clean and, by preventing wolves from eating livestock, draw clearer boundaries between nature and humans.

“All these ranchers complaining about attacks are ultimately feeding the wolves,” he says. “It’s very nice of modern society to say they want wolves alive, but just protecting them is not enough. Keeping wolves alive requires actively managing nature—and paying for it.”

--With assistance from John Ainger.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.