Nov 18, 2021

In Prison Note, Georgian Ex-President Says U.S. Must Intervene

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Imprisoned and on hunger strike, Georgia’s former President Mikheil Saakashvili called on the U.S. for help as the former Soviet republic turns away from the pro-Western path he set it on 18 years ago.

Saakashvili sent the scrawled, handwritten responses to questions through his lawyers Wednesday. Now 48 days into a hunger strike in which he drinks but does not eat, a doctor told reporters outside the hospital Thursday the 53-year-old temporarily lost consciousness during the day but was now stable.

In his notes, the former president said he had been beaten and dragged across asphalt to orchestrated taunting by inmates while in prison. The government refused to move him to a civilian hospital, give him a phone or even let him attend his own trial, Saakashvili wrote.

He said he returned ahead of local elections in October because a combination of “Russian games” and government statements had convinced him the nation of 4 million was abandoning its goal of joining the European Union and NATO.

“If the U.S. doesn’t come to my defense it would be a terrible signal to all pro-Western leaders and populations” in the region, wrote Saakashvili. He was arrested on Oct. 1 for crossing the border illegally and jailed to serve a previous in-absentia conviction for abuse of office.

The justice ministry said the minister was unavailable for comment on Saakashvili’s claims. A spokeswoman for the ruling Georgian Dream party declined to comment.

A cordon of police kept scores of the former president’s supporters and the media away from the jail in the suburbs of the capital Tbilisi.

Saakashvili’s imprisonment comes at a time when Western resolve is being challenged across the former Soviet Union in the face of an increasingly assertive Russia. Reports of troop concentrations have prompted a U.S. warning the Kremlin may plan a further invasion of Ukraine. At the Polish-Belarus border, embattled leader Alexander Lukashenko has been driving migrants toward the EU.

Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili’s government has been dismissive of Western criticism, arguing Georgia should follow its own culture and path. However, it still supports Georgia’s ambitions to join European institutions.

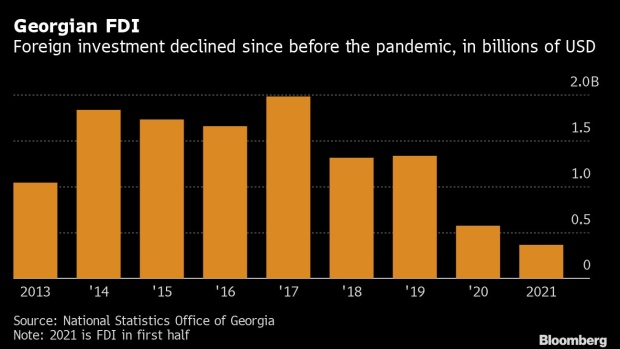

Foreign investors, once drawn to the relatively uncorrupt business environment that was among Saakashvili’s more positive legacies, have begun to stay away. Direct foreign investment in the first half was the lowest in more than a decade.

Last year’s decision to pull the plug on a large U.S.-backed plan for a deep port at Anaklia on the Black Sea has been a particular disincentive for new investment, according to Giga Bedineishvili, dean of the school of business at Tbilisi’s Free University. The project, now the subject of international arbitration, had strategic implications for Georgia as a trade route and potential berth for NATO naval vessels. It was opposed by Russia.

Georgian Dream, still heavily influenced by its billionaire founder and former Prime Minister Bidzina Ivanishvili, has sought to improve relations with Moscow. Those went into a deep freeze after a 2008 war that Saakashvili fought resulted in Russian occupation of two separatist territories of Georgia.

Georgia’s current President Salome Zourabichvili, who ran for the presidency as an independent, has frequently clashed with Saakashvili. Still, on Wednesday she criticized the government for failing to provide reliable information about his health and the extent of prison medical facilities. “A country whose territories are occupied and whose goal is European integration is under both special observation and threat,” she said.

Saakashvili said his experiences made him regret not doing more to reform the country’s prisons and court system, the state of which were factors that contributed to his downfall in 2013.

A committee of doctors formed by the Georgian ombudsman said after a visit Wednesday night that he should be immediately transferred to a hospital with full intensive care facilities.

It wasn’t clear Thursday how the government would respond to the doctors’ call to hospitalize the former president. “The hunger strike of Saakashvili is fake and whatever the committee did was fake,” Irakli Kobakhidze, secretary of Georgian Dream, said in televised remarks.

The government has cause for concern; there have been regular street protests calling for Saakashvili’s release since he was jailed. He first came to power in the so-called Rose Revolution in 2003, when he stormed the parliament in Tbilisi at the head of a crowd and deposed then President Eduard Shevardnadze.

It was the first in a series of so-called color revolutions in the former USSR that occurred in Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan and Armenia. All were pro-democracy protests, often claiming election fraud, that became a major source of friction between the West and Russia, which accused the U.S. of fomenting them. The most recent attempt, in Belarus last year, failed to oust the government.

Georgia’s opposition says October’s municipal elections – in which Georgian Dream won all but one contest – were falsified. International observers said the vote was “competitive” and “generally well administered,” but that the process also was tilted toward incumbents by an imbalance of resources as well as intimidation.

Asked if he thought his supporters should try a repeat of 2003, Saakashvili replied only that the government was “terribly afraid of my public appearance, because it would galvanize the crowds.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.