Mar 21, 2024

Canada plans to cut temporary residents by 20% over three years

, Bloomberg News

Growing skepticism about immigration is a real political economy threat: Sean Speer

Canada, a country that’s relying heavily on immigration as an economic driver, is scaling back on its ambitions with a planned reduction in temporary residents after the influx exacerbated housing shortages.

The country will set a target for temporary resident arrivals for the first time later this year, with the goal of reducing the number by about 20 per cent over the next three years, Immigration Minister Marc Miller said at a briefing on Thursday in Ottawa, alongside Employment Minister Randy Boissonnault.

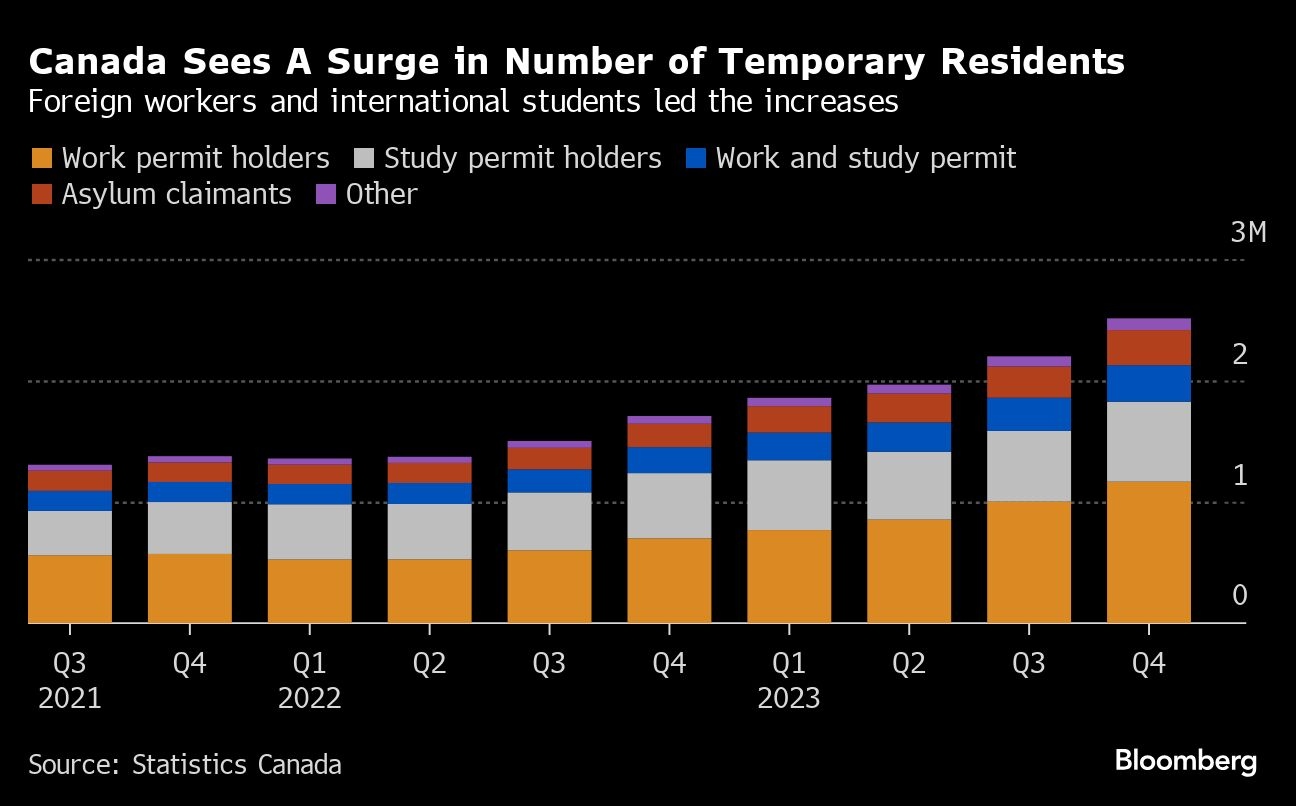

Currently, there are more than 2.5 million temporary residents living in the country, or 6.2 per cent of the population. The government aims to decrease the temporary resident population to 5 per cent, or about 2 million, “in order to reach an adequate volume of temporary residents Canada can welcome,” Miller said.

The new annual target will allow control over the number of temporary immigrants — including foreign workers, international students and asylum claimants — which has been growing rapidly in recent quarters. Previously, the Canadian government only set annual targets for permanent residents, aiming to bring in about half a million of them annually.

“This will help strengthen the alignment between immigration planning, community capacity and labor market needs and support predictable population growth,” Miller said.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government has made immigration a key pillar of economic policies to stave off declines from an aging population and falling birth rates. As a result, Canada’s populace has been growing at a record pace, now among the world’s fastest at annual rate of 3.2 per cent. Its population surpassed 40 million in June, and is now approaching 41 million just nine months later.

While recent inflows helped the economy avoid a downturn amid elevated interest rates and boosted labor supply, the rapid increases added strains on infrastructure and services, worsened housing shortages and sent rents soaring. Rising frustration over the cost of living and growing criticisms against Trudeau’s immigration policies forced the government to try to slow down the arrivals of newcomers.

Earlier this year, the immigration minister cut the number of international student permits for 2024 by 35 per cent from 2023 levels. In November, he said the government will stabilize the number of permanent residents at a record half a million per year, the first time in a decade that the government didn’t raise its annual targets.

Last month, Miller said in an interview with Bloomberg News that Canada has “gotten addicted to temporary foreign workers” and that the government is taking steps to curb that dependence. Canada’s challenge is balancing economic needs with preserving the country’s relatively orderly immigration system, which has seen a loss of public support in recent months.

“Ottawa should be careful placing arbitrary immigration caps. Temporary residents are a critical pool of talent for some sectors of our economy,” said Diana Palmerin-Velasco, senior director for the future of work at the Canadian Chamber of Commerce. “The reality is that we currently have more than 600,000 unfilled job vacancies across the country negatively impacting our ability to grow our economy.”

To set the new target, Miller will convene a meeting with his provincial and territorial counterparts, as well as other relevant ministers, in early May.

He also said his department will review existing streams that bring in temporary workers to ensure that they are better aligned with labor market needs and to “weed out abuses in the system.”

According to the employment minister, Canada will reduce the number of temporary foreign workers entering the country starting May 1. Employers in food manufacturing, wood product and furniture manufacturing, as well as accommodation and food services, will only be allowed to have 20 per cent of their workforce come from the low-wage stream of the program, down from 30 per cent.

The reduction will likely affect owners, operators and franchisees of restaurants or fast-food chains. The 30 per cent cap will remain in place for employers in health care and construction sectors, at least until Aug. 31.

Boissonnault also announced that the validity period of labor market impact assessments — basically documents showing no Canadian is available for the job — will be shortened to six months from one year. Employers will also be required to show that they offered the position to asylum-seekers and other underrepresented groups before applying for the program.

“The temporary foreign worker program is a last resort,” Boissonnault said.

“Employers should not use the temporary foreign worker program as a means to avoid offering competitive wages to Canadians. They need to innovate and invest in the workforce to make sure that Canada is productive and our country continues to grow.”