A world economy already contending with raging inflation, stock-market turmoil and a grueling war is facing yet another threat: the unraveling of a massive housing boom.

As central banks around the globe rapidly increase interest rates, soaring borrowing costs mean people who were already stretching to buy property are finally reaching their limits. The effects are being seen in countries such as Canada, the US and New Zealand, where once-hot residential real estate markets have suddenly turned cold.

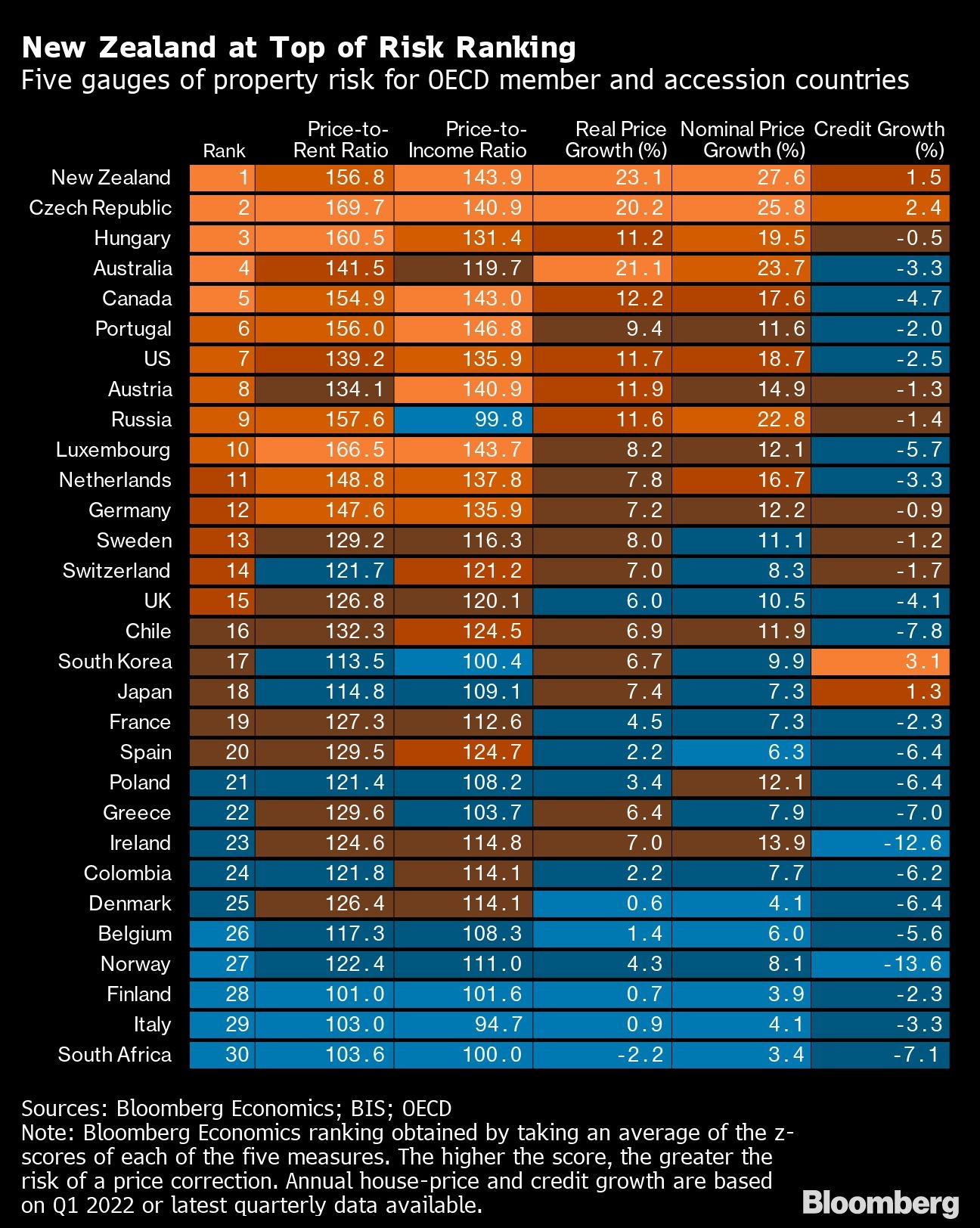

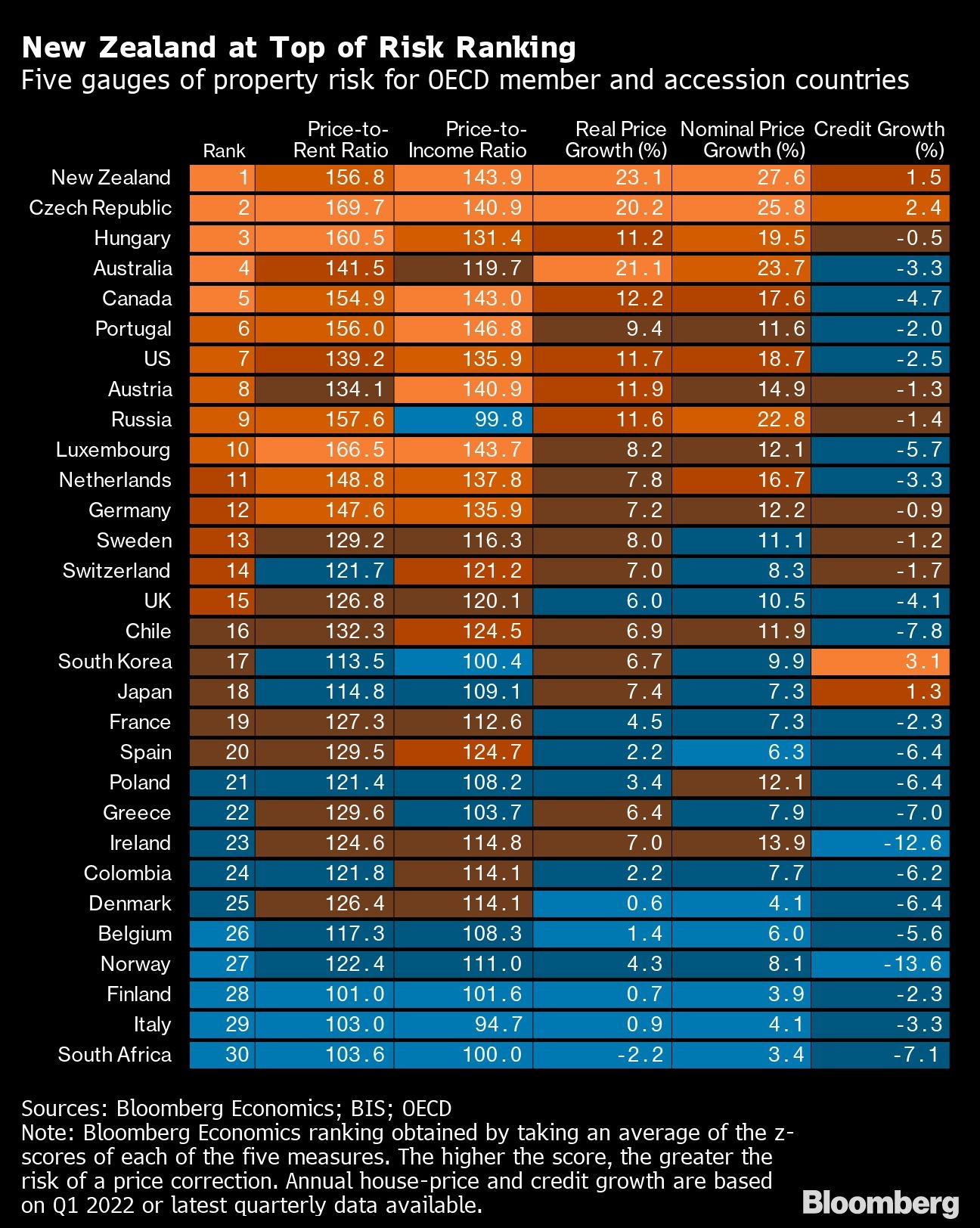

It’s a sharp reversal from years of surging prices fueled by rock-bottom mortgage rates and government stimulus, along with a pandemic that popularized remote work and sent homebuyers on the hunt for bigger spaces. An analysis by Bloomberg Economics shows that 19 OECD countries have combined price-to-rent and home price-to-income ratios that are higher today than they were ahead of the 2008 financial crisis — an indication that prices have moved out of line with fundamentals.

Taming frothy home prices are a key part of many policy makers’ goals as they seek to quell the fastest inflation in decades. But as markets shudder from the prospects of a global recession, a slowdown in housing could create a ripple effect that would deepen an economic slump.

Falling home prices would erode household wealth, dent consumer confidence and potentially curb future development. Animal spirits are typically tamed when people are faced with higher repayment costs on an asset that’s losing value. And property construction and sales are huge multipliers of economic activity around the world.

“The danger is business and financial cycles turning down simultaneously, which can lead to longer-lasting recessions,” said Rob Subbaraman, head of global markets research at Nomura Holdings Inc. “A decade of QE has fueled frothy housing markets and we could be entering the other side of this soon, as housing affordability is stretched and debt-service ratios could rise sharply.”

Such a scenario would gum up bank lending as the risk of bad loans increases, choking the flow of credit that economies thrive on. In the US and Western Europe, the housing crash that precipitated the financial crisis hobbled banking systems, governments and consumers for years.

To be sure, a 2008-style collapse is unlikely. Lenders have tightened standards, household savings are still robust and many countries still have housing shortages. Labor markets are also strong, providing an important buffer.

“Lower prices will have a direct effect on consumer spending and the whole economy, as typically real estate makes up a significant part of households’ wealth,” said Tuuli McCully, head of Asia-Pacific economics at Scotiabank. “Nevertheless, as household balance sheets in many major markets remain healthy, I am not particularly worried about risks related to house prices and the world economy.”

Still, the risk of a sharp drop in prices is clearly greater when there’s a synchronized global tightening of monetary policy, said Niraj Shah of Bloomberg Economics in London. More than 50 central banks have raised interest rates by at least 50 basis points in one go this year, with more hikes expected. In the US, the Federal Reserve last week boosted its main interest rate by 75 basis points, its biggest increase since 1994.

Housing markets in New Zealand, the Czech Republic, Australia and Canada rank among the world’s bubbliest and are particularly vulnerable to falling prices, according to Bloomberg Economics. Portugal is especially at risk in the euro area, while Austria, Germany and the Netherlands also are looking frothy.

In Asia, South Korea house prices also look vulnerable, according to an analysis by S&P Global Ratings. That report noted risks from household credit relative to nominal GDP, the growth rate of household debt and the speed of house-price gains. Elsewhere in Europe, Sweden has seen a dramatic turnaround in housing demand, sparking concern in a country where debt runs at 200 per cent of household income.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. economists wrote in a report last week that the signals from home sales typically precede prices by about six months, indicating that several countries are likely to see further declines in values. A substantial cooldown in housing markets is an important reason why developed economies will likely slow, according to the economists led by Jan Hatzius.

“The very rapid deterioration in affordability and large drops in home sales suggest that a hard landing is a meaningful risk, especially in New Zealand, Canada, and Australia, although that is not our baseline given current tightness," the Goldman economists wrote.

Central banks are issuing warnings of their own. The Bank of Canada said this month in its annual review of the financial system that high levels of mortgage debt are of particular concern as interest rates rise and more borrowers are strained to pay bills. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s semi-annual Financial Stability Report said that the overall threat to the financial system is limited, but a “sharp” decline in house prices is possible, which could significantly reduce wealth and lead to a contraction in consumer spending.

“As borrowing costs rise, real estate markets face a critical test,” Bloomberg's Shah said. “If central bankers act too aggressively, they could sow the seeds of the next crisis.”

Here is what’s unfolding in bubbly housing markets around the world.

NEW ZEALAND

If 2021 was the year New Zealand’s house-price growth reached dizzying heights, with an annual increase of close to 30 per cent, 2022 is shaping up to be the year the music stops — and the abrupt change has left people scrambling.

In March, Jonathan Milne decided it was time to sell a family home in the Auckland suburb of Onehunga and purchase a larger house nearby for NZ$2 million (US$1.3 million). He and his wife, Georgie, were optimistic of a speedy sale and a good price for their old home, which was valued by the local government at NZ$1.8 million.

All that changed in April when the RBNZ took aggressive action to tackle inflation, hiking the official rate by 50 basis points to 1.5 per cent — its biggest increase in 22 years. It quickly followed with another 50-basis-point jump in May and a projection for the rate to peak at close to 4 per cent next year.

Milne’s house was meant to be sold in May via auction, a popular method of home sales in New Zealand, but not a single bidder showed up for the event.

“What we didn’t anticipate was that it would be so hard to market and sell our house,” said Milne, the 47-year-old managing editor of a news website. “We knew that every week that passed would knock another NZ$100,000 off the price.”

At the end of last month, they accepted an offer that Milne described as “dramatically” below the government valuation.

Economists expect New Zealand house prices will fall about 10 per cent this year and may eventually drop as much as 20 per cent from their late 2021 peak. While for many homeowners that’s a small decline compared with the massive equity gains in recent years, there likely will be broader effects. ANZ Bank forecasts subdued consumer spending due to a mixture of people feeling poorer because of falling house prices, the impact of higher rates on cash flow, as well as higher food and energy prices, according to Sharon Zollner, the bank’s New Zealand chief economist.

“There are going to be house buyers who have just entered the market in the last year or so who started off with a mortgage rate of 2.5 per cent and all of a sudden they are rolling off on to a mortgage rate closer to 6 per cent,” said Jarrod Kerr, chief economist at Kiwibank in Auckland. “There is going to be some pain for sure.” — Ainsley Thomson

CANADA

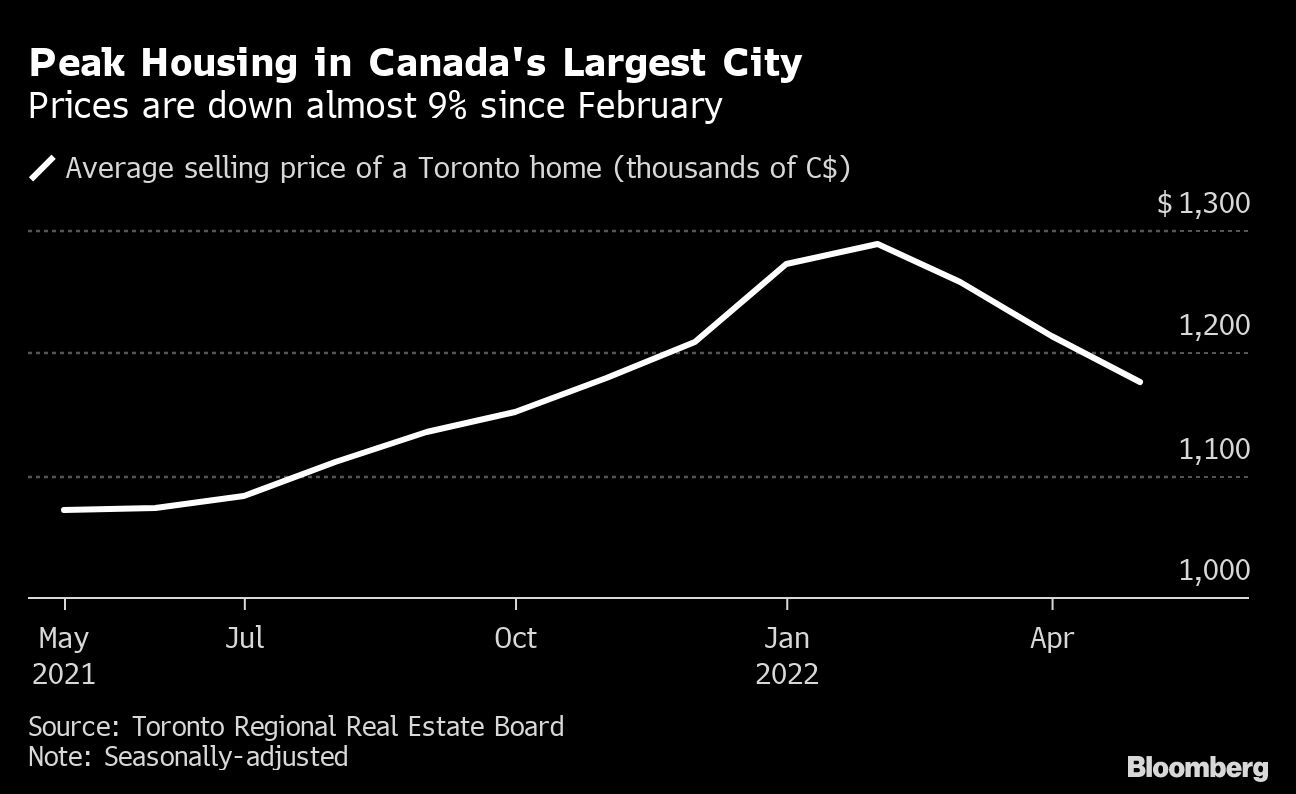

The housing market in Canada has turned so fast some buyers are losing money on their properties before the sales even close.

“People are actively trying to get out of deals,” said Mark Morris, a Toronto-based real estate lawyer who cited one example where a property’s assessed value came in $200,000 (US$155,000) less than the purchase price agreed to only a couple months before. That left the buyer willing to give up their $100,000 deposit to avoid closing, he said. “I’m called several times a day by various people who feel that they’ve paid too much.”

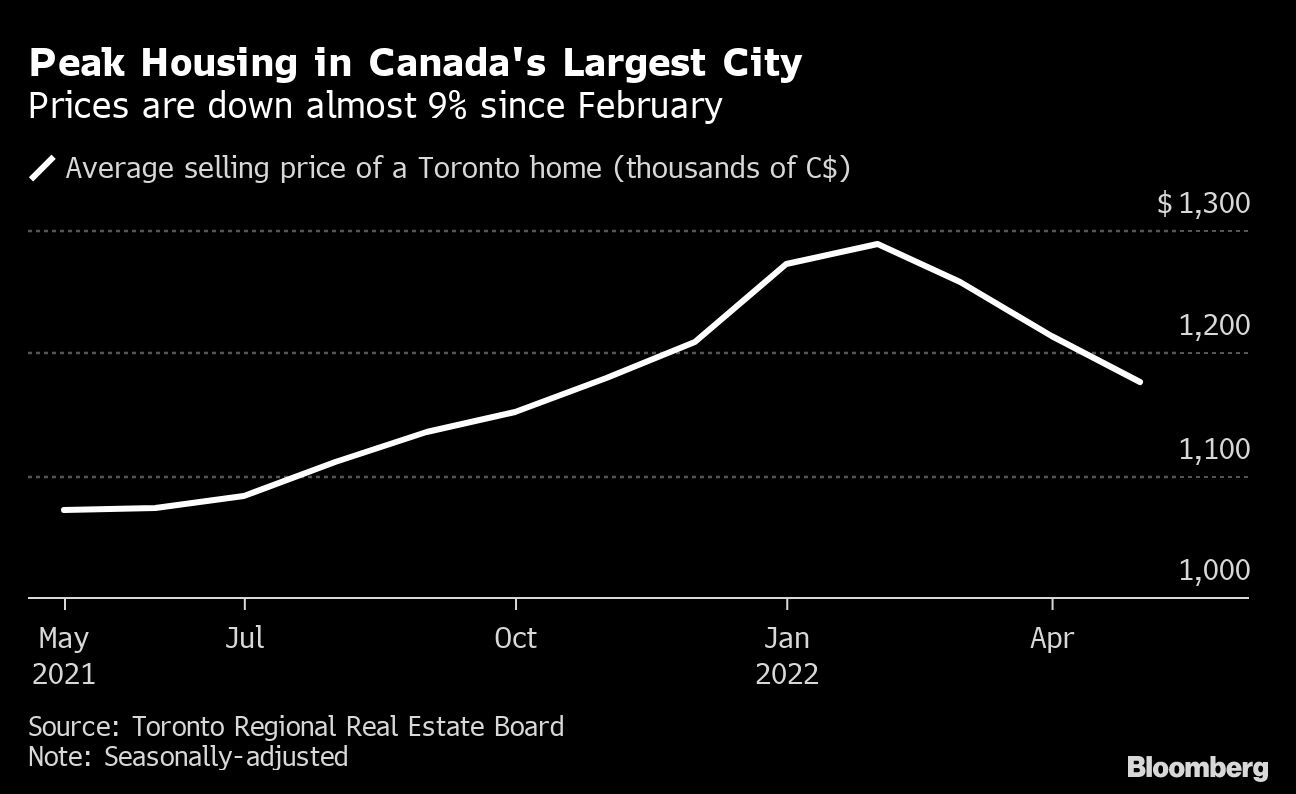

Such cases are cropping up after Canada posted its first national home-price decline in two years in April, followed by another drop in May. Though so far the pain has been concentrated around the markets which saw the biggest pandemic runups — Toronto and its surrounding regions — the strains are already starting to spread to formerly hot markets around Vancouver too.

Like in other countries, the turmoil in Canada’s housing market is being caused by an aggressive campaign to raise interest rates by the central bank. The benchmark has already gone from 0.25 per cent at the beginning of the year to 1.5 per cent today. With even higher rates expected, some economists say home prices could fall as much as 20 per cent in the hottest markets.

It’s a drastic change in a country that saw prices rise by more than 50 per cent over the two years since the pandemic started. With prices rapidly outpacing wage growth, some buyers’ hope of entering the market came from low rates that are now jumping.

“It’s the marginal buyer who’s supporting current valuations, so that could mean significant impact on the housing market,” said Matthieu Arseneau, deputy chief economist at National Bank of Canada, who says home prices nationally could fall as much as 10 per cent. “Will new buyers be able to afford those prices at these rates?” — Ari Altstedter

U.S.

Mabel Melendi could tell the housing market in Cape Coral, Florida, was slowing after a week went by and she still hadn’t received any inquiries or offers on a newly constructed home she listed in mid-April. Just three months ago, she received a bid on a similar property within three days of putting it on the market.

But after three price cuts — knocking the asking price down to US$425,000 from US$510,000 — and more than two months after the initial listing, she was still looking for buyers in mid-June. One offer that came in over Memorial Day weekend fell through after the buyer couldn’t qualify for a large enough mortgage.

“Most of the people don’t qualify for what they used to qualify for before,” Melendi said.

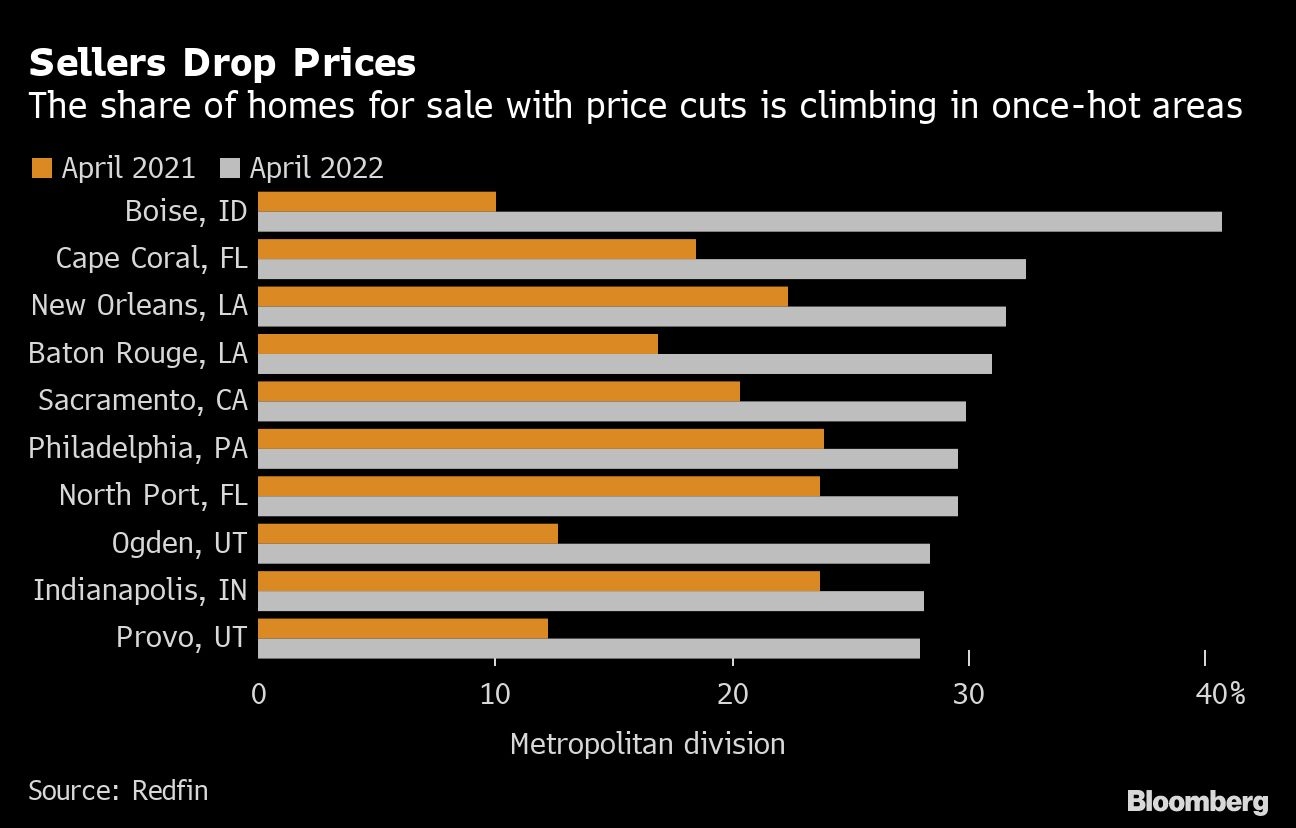

Mortgage rates have increased this year at the fastest pace in records dating back a half century, according to Freddie Mac. The average rate for a 30-year loan reached 5.78 per cent last week, the highest since 2008. That’s led to price cuts for both builders and existing-home sellers as demand rapidly cools.

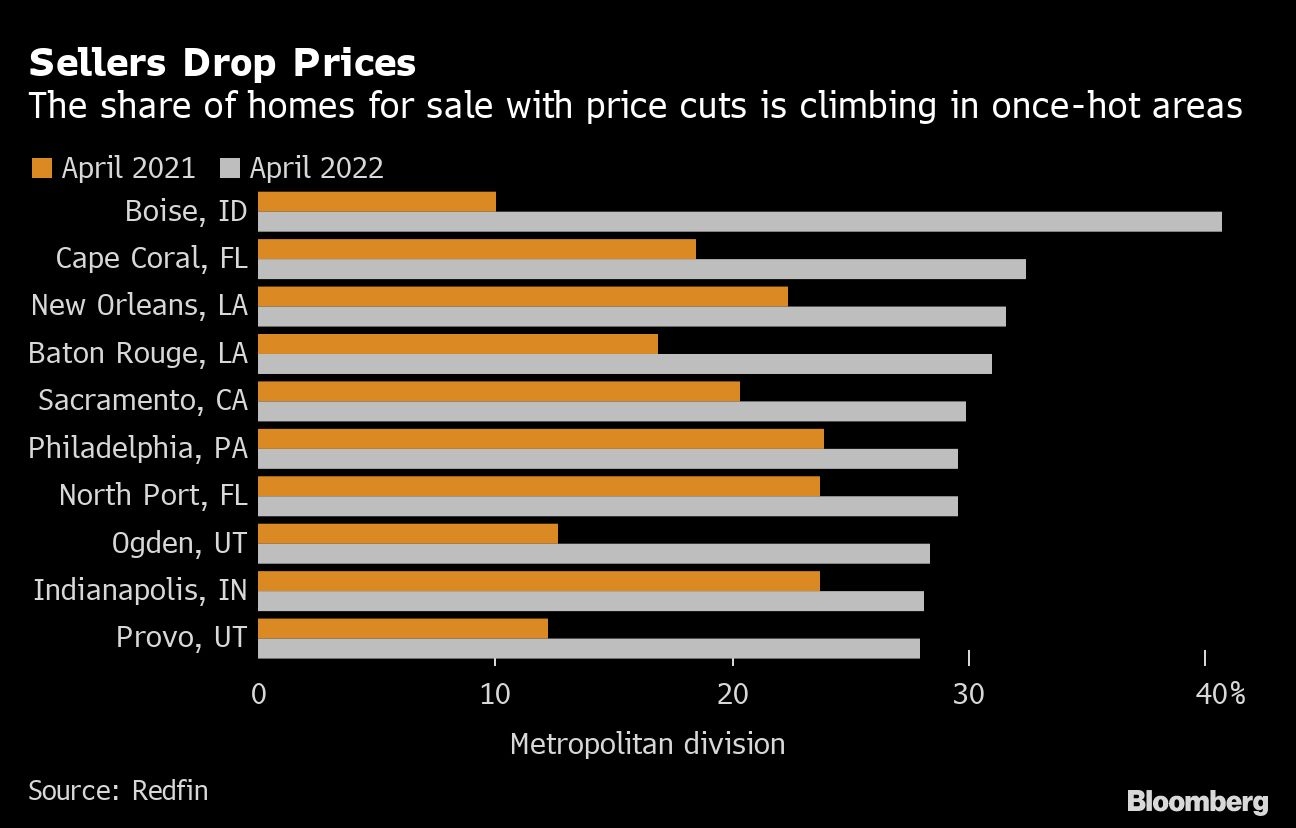

Almost 20 per cent of US home sellers cut prices in the four-week period ended May 22, the most since October 2019, according to the brokerage Redfin Corp. The share was higher in some markets that became hot destinations during the pandemic for people seeking more affordably-priced homes. In Boise, Idaho, for example, 41 per cent of sellers dropped prices in April. In Cape Coral, it was about one in three.

Sellers are realizing that prices may not keep rising at the same pace they previously did as buyers are increasingly squeezed, said Daryl Fairweather, Redfin’s chief economist. “Prices are going to have to come down to match demand,” she said.

After rising by an estimated 18 per cent in 2021, US single-family home prices are forecast to grow by a more moderate pace of 10 per cent in 2022 and 5 per cent in 2023, according to Freddie Mac. “It’s a pretty significant slowdown, but coming from scorching-hot house-price growth,” said Len Kiefer, the company’s deputy chief economist. A shortage of homes for sale and pent-up demand from people seeking more space — along with millennial buyers getting older and starting families — means prices nationally should still trend higher, he said.

Still, the effects of slowing demand are reverberating through the real estate industry: Redfin and Compass Inc. said last week that they will lay off employees after the sudden cooldown in the market. — Jonnelle Marte

CZECH REPUBLIC AND HUNGARY

The Czech Republic stands out in Europe for its high homeownership rate, fast inflation and low unemployment, said Vit Hradil, a senior economist with Prague-based investment firm Cyrrus. Combined with a uniquely complex construction permit system and growing demand from expats seeking work in the capital, the country has faced staggering price increases that have far outpaced income growth.

A quarterly gauge of Czech house prices rose 26 per cent in the December from the previous year, according to London-based data analysis company CEIC Data. The difference between an average citizen’s income and real estate prices in the country is now one of the widest in the European Union, raising serious bubble fears.

To tame inflation that reached 16 per cent in May, the Czech central bank has been on a monetary tightening campaign that lifted interest rates to the highest level since 1999, before another meeting this week.

“You would expect these rates to cool demand but, with inflation rates that much higher, it’s not working,” said Hradil, who added that people in the country see housing as an inflation hedge and prefer investing in real estate rather than stocks.

In Prague, video-effects producer Meera Sankar gave up on buying a home. Initially aiming to find a one-bedroom apartment in the city center for 3 million koruna (US$130,000), the Ireland native eventually doubled her budget, but still couldn’t find an apartment that met her criteria. What she found either needed complete renovation or was in a remote or relatively unsafe area.

“For this kind of money you can get a huge four-bedroom house near Cork, Ireland, or a 150-square-meter apartment in my dad’s hometown in India,” she said. “It just doesn’t add up.”

The Czech Republic ranks second on Bloomberg Economics’ bubble measure, followed by its regional neighbor, Hungary. There, Prime Minister Viktor Orban has pushed homeownership incentives in a bid to boost fertility rates.

Prices in the country increased almost 20 per cent in the last three months of 2021, compared with the same period a year earlier, according to the European Union’s data agency Eurostat. The situation has only been exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, which has pushed up energy costs and limited construction-worker availability. Last week, the central bank unexpectedly raised the key interest rate by 50 basis points. — Alice Kantor

U.K.

The UK housing market is starting to slow after two years of historic growth. As part of pandemic measures, homebuyers were exempt from a stamp tax duty on properties valued at up to £500,000 (US$614,000) between July 2020 and June of last year, sending prices escalating even further and making housing “seemingly detached from the rest of the economy,” said Tom Bill, head of UK residential research at Knight Frank.

Now, the Bank of England has increased rates five times in recent months, with more hikes expected to come. That may portend a cooldown in real estate for the rest of the year, with more supply becoming available as homeowners rush to beat declines in values, Bill said.

Already, approvals for new home loans have dropped to the lowest in almost two years. Buyer inquiries fell in May after gaining for eight straight months, according to a survey from the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors.

“People are worried about the economy, about how the war in Ukraine will affect prices and the rising cost of living,” said Aneisha Beveridge, head of research at UK real estate company Hamptons International. “They’re more cautious.”

The Bank of England decided this week to scrap affordability tests, which gauge borrowers' ability to repay their mortgages, as of Aug. 1. That could increase the risk of first-time homebuyers making purchases they can't afford.

Still, areas such as prime London are faring well, Bill said, as foreign investors flock to the international destination and students return following the pandemic. Secondary cities like Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester are seeing their prices grow even faster than in the capital.

“As long as the UK is seen as a country with a rule of law, good schools, and the respect of private property, money will always flow in,” Bill said. — Alice Kantor