Apr 17, 2024

BPI’s Bill Nelson Sees Fed Pushing Reserves Below Resistance Point

, Bloomberg News

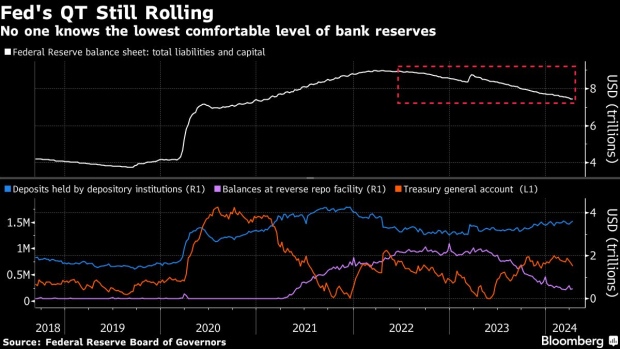

(Bloomberg) -- As the Federal Reserve shrinks its balance sheet, there’s a chance policymakers will keep unwinding passed the point of scarcity in reserve balances, according to Bill Nelson, head of research at the Bank Policy Institute.

Remarks by the former Fed economist are the latest to surface as Wall Street and the US central bank focus on what level of bank reserves is appropriate to guarantee liquidity and avert blowups in financial markets. The amount of cash institutions have parked at the Fed stands at nearly $3.62 trillion. That’s a level policymakers characterize as abundant, and they’re aiming for ample, which Chair Jerome Powell defined at last month’s press conference as “a little bit less” than that.

“Based on market participants and based on past experience and how demand moves up, it’s reasonable to think the Fed will start to meet resistance around $3 trillion, but it’s not where they need to stop,” Nelson said. The US could follow the desire of other central banks to push for a smaller balance sheet rather than stop at the first point of resistance, he said.

Nelson appeared with Bank of America Corp.’s Mark Cabana on a panel hosted by the Money Marketeers of New York University Inc. earlier this week. Cabana argued that the Fed will opt for a more wait-and-see stance, prioritizing smooth running markets and avoiding the need for emergency measures to rescue the financial system.

Central banks around the world are trying to gauge how far they can shrink their balance sheets before sending overnight markets into a tailspin. Recently the Bank of England, European Central Bank, Bank of Canada and Reserve Bank of Australia have all indicated they intend to operate on a floor system, where there’s just enough reserves to satisfy demand.

The Fed has been winding down its holdings of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities — a process known as quantitative tightening, or QT — at a rate of as much as $95 billion per month. At their March gathering, policymakers began discussing plans for slowing down the process, though no decisions were made at the meeting.

Although most officials saw the process as proceeding smoothly, they “broadly assessed” it would be appropriate to take a cautious approach to further runoff given market turmoil in 2019, the last time the Fed tried to shrink its portfolio, according to minutes from last month’s meeting. The vast majority of participants judged it would be prudent to begin slowing the pace “fairly soon.”

Read more: New York Fed Says Quantitative Tightening Could Stop in 2025

For now, short-term funding markets have been stable and stress free, which offers considerable flexibility as officials consider the path ahead for QT. If the Fed lets reserves shrink too much it risks triggering volatility in overnight funding markets similar to what was seen in September 2019. However, too many reserves consume bank capital and inhibit lending, and ensure the Fed bank maintains a large footprint in the Treasury cash and repo markets.

Cabana, head of BofA’s US interest rates strategy, said the firm sees the optimal level between $3 trillion and $3.25 trillion, citing the responses in the Fed’s latest Senior Financial Officer survey.

Conducted in September, the survey also found about 65% of bank treasurers expected their balance sheets to be roughly unchanged over the next six months, that’s up from nearly one-third in the prior survey.

“Bank demand for reserves is dynamic, not static,” he said. “The current interest rate, macroeconomic and regulatory environment is incentivizing banks to hold more reserves than they need to.”

Yet Nelson isn’t convinced that the Fed will be willing to stop QT once reserves hit the lower band. There are sources of funding that could motivate banks to reduce the amount of cash they’re parking at the central bank. For instance, changes to treatment of the discount window, de-stigmatizing its use as a funding facility of last resort, could spur institutions to hold fewer reserves without triggering a liquidity crisis, he said.

Cabana, however, said going back to a time when reserves were more scarce still poses the risk of volatility in money-market rates.

“We could go back but the Fed would have a lot less money-market control,” he said. “I’d be surprised if the Fed would be willing to accept that cost.”

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.